Types of knowledge and what they allow us to see

How our research methods affect the quality of our psychological understanding

by Matthijs Cornelissen

(DRAFT: last update 2/2/2012)

- Introduction

- Part I: Four approaches to understanding human nature that are part of mainstream psychology

- Part II: The four knowledge realms that are needed for a comprehensive understanding of human nature

- Part III: An approach to Psychology with roots in the Indian tradition

- To Conclude

- Endnotes

- References

Introduction

In ancient Greece, Know Your Self, gnooti seouton, is said to have been inscribed above the entry of Plato's Academy and Delphi's Oracle. The Indian tradition credits knowledge of the Self with nothing less than providing inalienable delight, immortality, and the knowledge that makes all things known1.

Coming to us with such unbeatable credentials, one would expect knowledge of the self also to get the highest priority in modern Psychology, but, strangely, this has not been the case. In fact, since the publication of Watson's Psychology as a Behaviourist sees it, now almost 100 years ago, enquiry into oneself has been systematically discredited by psychologists as subjective and unscientific.

American Psychology took this amazing turn in response to a methodological conundrum, in which reliability and measurability were chosen over meaning and relevance. It appears that the psychologists of the time considered only one type of knowledge reliable enough to be part of science, and this was the rational analysis of explicit statements derived from the objective measurement of simplified physical phenomena, the type of knowledge that had worked such wonders in the hard sciences. Unfortunately this kind of third-person, “objective” knowledge is not sufficient for the study of psychology as there is no place in it for awareness, agency, happiness, love, beauty, meaning, and all those other typically human things which are quintessentially subjective and first-person, having consciousness as their key-ingredient.

What I'll try to show here is that a more integral and wholesome answer to Psychology's quest for an appropriate methodology is possible, but that it has to be found outside the narrow limits of contemporary science. Fortunately, science in its present form is not the only sophisticated knowledge system available in our global civilization and in the Indian tradition one can find a radically different system that has specialised in the systematic study of consciousness. It offers a deep theoretical and philosophical understanding of knowledge types that are not used in science at present, but that are crucial for the further development of psychology. It has also developed practical ways to hone and perfect them to a degree that should satisfy the scientific demand for rigour and precision. In the first part of this article I will present a birds-eye view of four mainstream approaches to psychology; in the second part I will give a short overview of the additional knowledge types the Indian tradition has developed, and then in the third part I will indicate in very short the aspects of reality they can help us to explore.2

Before we get to the real argument, it will be good to realise that reality is far more complex, subtle, flexible, and beautiful than whatever mental representation we can make of it. This is perhaps even more true for pictorial diagrams than for text. Still, as pictures “say more than a thousand words”, I've built this exposition around six diagrams explaining which part of reality different approaches to psychology make available to us, but they should not be taken too seriously! We should especially avoid reifying the things and processes they point at: words and pictures have their utility, and even their charm, but they are not reality.

PART I: FOUR APPROACHES TO UNDERSTANDING HUMAN NATURE THAT ARE PART OF MAINSTREAM PSYCHOLOGY

Behaviourism phase one: animal experiments

We will start then with a diagram showing the universe as seen by the classical behaviourist. It is reassuringly simple: all we can know scientifically is physical behaviour in a purely physical universe. As far as thoughts, feelings, ideas etc. exist, they cannot be known scientifically and so they are left out from the picture. I've drawn a thick line around the behaviourists' universe to indicate that behaviourists tend to be very clear about what they admit within their researchable universe and what not. What exactly is included differs, however, from one behaviourist to the other. Initially, for Watson, the only thing included was physically observable behaviour. Everything else, including thoughts, feelings, intentions, consciousness, was out. Over time more and more things were permitted within the box, and behaviourism is now sometimes simply defined as the study of everything the individual “does”.

There are a few things that deserve to be noted about behaviourism, even in this very short overview. The first is that it is hard to exaggerate its influence on academic psychology as taught at universities the world over: while until 1913, psychology had been known as the science of consciousness, after 1913 it became almost univocally the science of behaviour, and even now, 100 years later, it is hard to find an introductory textbook of psychology that does not contain the world “behaviour” in its definition of psychology.

The second is that the positivist philosophy of behaviourism is entirely non-reflexive: it is a “view from nowhere”, as Nagel called it. It distrusts subjective experience and agency on the side of the researcher, and it studies only the behaviour and manipulation of others. There are many difficulties with this. The main one may well be that people don't like to be manipulated or treated as objects. Another one is that it is a denial of the simple fact that we know the world only through our own nature, our own inner “instruments of knowledge”. Pretending that our nature is a perfect instrument, and not in need of any further enquiry is unbelievably naïve.

The third point, related to the second, is the dominance of animal studies related to learning and motivation. The most serious problem with this is that the results were generalized to the way children learn.3 Psychology is the fundamental science on which education is based, and during much of the last hundred years, trainee teachers, the world over, have been steeped in behaviourist psychology. As a result, behaviourist studies of rats have reinforced a system of education that replaces the natural learning of children, which consists of happy, playful attempts at making sense of their existence in the world, by learning of for the child arbitrary, meaningless facts under the pressure of a reinforcement regime that consists of deprivation, punishment and secondary rewards. In other words, children are taught throughout their formative years to do meaningless things in order to obtain “incentives” in an overall climate of deprivation. This is not a minor, innocent error. Though hard to prove and quantify, it must have contributed considerably to the alienation and obsessive production and consumption that threatens to ruin our beautiful planet.

Behaviourism phase two: Surveys

Given the extreme poverty of the classical behaviourist's universe, an expansion was needed, and it was found in the form of self-reports that can be measured simply and reliably. In mainstream American psychology, these self-reports typically consist of Likert scales: lists of carefully selected statements, on which the subject can indicate to what degree he agrees or disagrees with them. It is understandable why such scales are attractive to psychologists: tick-marking a Likert scale is a unique form of behaviour that can easily and unambiguously be measured quantitatively, while it still has a link to more subtle psychological concepts like attitudes, traits, intentions, ideas etc.

Comparison with astronomy may make clearer why surveys are unlikely to take psychology much further. In astronomy, progress is made by providing a small number of exceptionally gifted and highly trained professionals with the best instruments society can afford, and the rest of us simply believe whatever they find. If mainstream, behaviourist psychologists had been in charge of this field, they might have argued that the findings of these astronomers have little interest or validity for the rest of us. They might have argued that their numbers are too small, and that their observations could be freak phenomena that cannot be verified, and that to get reliable data, we should instead administer questionnaires to representative sections of the world population and find out what these representative members of the general public see in the evening sky, as, after all, that is the sky that matters to them. Ignoring the numerically irrelevant astronomers, they might have studied whether there are statistically significant differences between the observations of city-dwellers, farmers and people living in the mountains.

One could look at this article as an attempt to explore what happens when one does the opposite, when one follows the astronomers' lead for psychology, and makes use of what a small number of gifted, well-trained and psychologically well-equipped specialists have to say about what happens in the human mind and spirit.

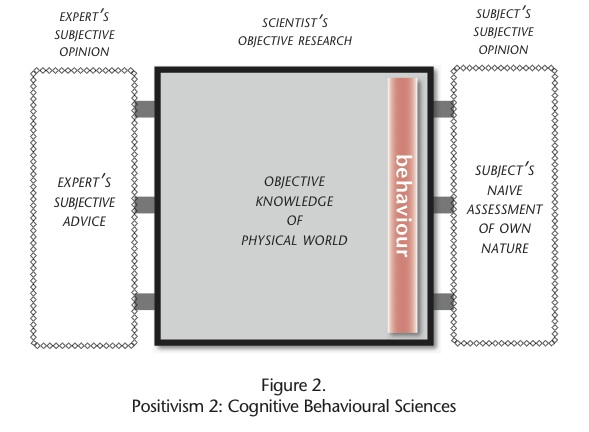

There are many problems with this kind of “quantitative” studies, but, as Figure 2 shows, there can be no doubt that they have expanded the psychologist's universe considerably. It may be noted that the scientist still considers his work to take place within the confines of positivism, as he limits himself to data he finds in the physical reality under his purview, and as he uses sophisticated techniques to measure and process them. Subjective judgments have, however, crept in from two sides. First, he has used either his own judgment or the subjective advice of subjectively chosen experts to create and validate the items in his scales. And second, his “objective” data now include reports produced by his subjects, who in their turn use naïve, unskilled introspection to generate these data. In other words, he has allowed entry to subjective judgment, but by two rather dubious, half-lit routes. The one we have depicted on the right is perhaps the most serious as the self-reports from the research-subjects are based on introspection while introspection is notoriously inaccurate. To compensate for the inaccuracy of individual reports, and of course to account for the large variety that is commonly found in psychological phenomena, psychologists typically use sophisticated statistical techniques to study relatively large “sample sizes”. The problem with this approach is, that even the most sophisticated level of processing cannot go much beyond the quality of the original data, and as a result, this kind of studies is not suitable for the discovery of new insights into the deeper, underlying psychological processes that determine what happens on the surface of our minds. All they can provide are insights into the geographical and social distribution of in itself low quality, naïve self-reports; in other words, what they provide is a sophisticated geography of simple psychological phenomena.

Social constructionism and qualitative research

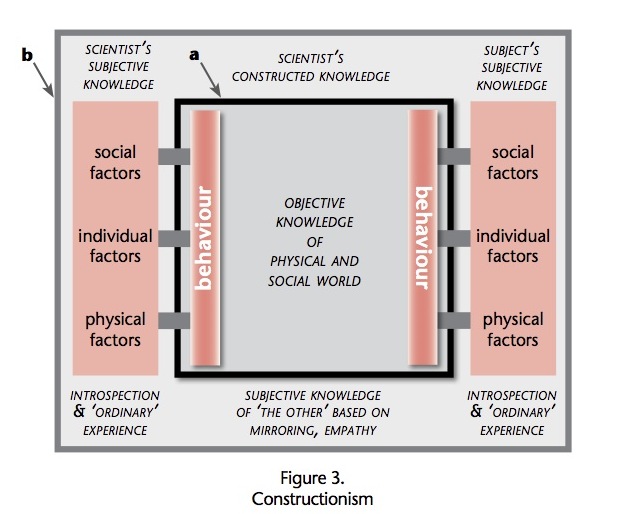

With the introduction of social constructionism, the world of psychology suddenly becomes considerably more complex. It is grounded in the idea that the researcher's social background has an inescapable influence on the findings he collects. As a result, the researcher becomes an acknowledged part of the research process and begins to be “problematized”. Constructionism is part of a more general trend to humanise the social sciences. It provides less scope for the treatment of “subjects” as if they were “objects”, and it facilitates a greater respect for alternate viewpoints, engendering social tolerance and cultural variety. One of the most valuable contributions of social constructionism is Piaget's cognitive constructivism: the realisation that children don't learn by simply “imbibing” prefabricated knowledge, but that they actively create their own knowledge through a complex creative process that needs to be respected and nurtured.

In this again highly simplified diagram, [a] delimits the outer physical world that can be studied with the help of our physical senses, reason, mathematics and whatever physical or mental instruments we can conceive, while [b] indicates the outer borders of the Social Constructionist's world. Subjectivity and experience are no longer shunned but acknowledged both on the side of the subject and the researcher. Clearly this deserves to be considered an enormous and valuable improvement over the simplistic world of behaviourism we started with.

Constructionism has spawned a whole range of new research methodologies that are often bundled together under the banner of “qualitative research”. Methods like narrative analysis, grounded theory and cooperative enquiry are all valuable extensions of our psychological repertoire. Still, all is not fine with constructionism.

The first problem is that constructions need a foundation, and constructionism seems to have no clue on where this foundation could possibly be found. As its opponents, and even some of its supporters have argued, if one applies constructionism to the scientific knowledge-generating enterprise itself and takes it to its logical conclusion, then everything you can get away with amongst your colleagues should be considered true (see Feiernabend (1975), quoted in Skinner 1985). Even before constructionism came up, it was often argued that in the end “consensus” amongst experts was the ultimate yardstick of science, but consensus is a risky criterion: within Nazi Germany there was an overwhelming consensus approving its racist theories, so, would these theories have been true if Germany had won WWII? Or to go further back, was the earth really flat when people believed that it was? The idea may be attractive to some, just as one could argue in favour of a public survey approach to astronomy, but still, relativism and trust in consensus don't seem to tell the whole story and it is not surprising that constructionism has encountered much opposition and even ridicule from the hard sciences. It is good to be aware of the power stuctures in which knowledge is embedded, and it is good to acknowledge the dangers of dogmatic “essentialism”, but still. While it can be admitted that all human knowledge systems are at least partially humanly constructed, they are also built on something. For the hard sciences that something is not too difficult to agree upon – both physically observable phenomena and mathematics have something “inevitable” about them -- but what that something could possibly be for psychology has till now escaped. The Indian tradition has found an interesting solution to this problem that allows one to escape from excessive relativism as well as from dogmatism. It states that there actually is one ultimate Truth, but that this Truth is intrinsically, and inevitably ineffable: there is in principle no single best way to express it. As a result, it is to be accepted, even celebrated, that different people express it differently.4 The value of this approach can only be appreciated if one realises that it comes from a cultural context in which several effective and logically convincing methods are available to increase the quality of one's approximations to that Truth. It is the combination of admitting ignorance and effective methods to decrease the degree of one's ignorance that provides hope for increasingly accurate approximations, while still respecting others for their views, however different they may be from our own.

There is another shortcoming of social constructionism in its present avatar and this is that it is still too limited to the “ordinary waking consciousness”, or OWC. From an Indian perspective, we could say that while constructionism has accepted the need to problematize the researcher's own knowledge-generating processes, its doubts and self-enquiries have not gone deep enough. They remain limited to the socio-political environment of the researcher but do not question the primacy of the sense-based ordinary waking consciousness that generates that socio-physical reality. Even in research about the effects of meditation, for example, the researchers normally don't leave their own OWC to do the research. There is hardly any research in which the pursuit of knowledge itself takes place within a state of meditation.5 In the very few cases where alternatives on the side of the researcher are attempted, things tend to become flaky. The reason for this is that there are no clear criteria on how to make these alternate knowledge generating and expressive processes more accurate.

If we are permitted once more a reference to the metaphor of astronomy, one could say that the result of all this is, that our present OWC-centred psychology is still as limited as medieval ego-centred astronomy was before Galileo and Copernicus.

Figure 3a. Mainstream psychology inhabits a Ptolemaic universe:

everything turns around the Ordinary Waking Consciousness

Or to say it differently, constructionism is, till now, still a flatlanders' world. It recognises that there are different viewpoints, but they are all still within one single plane.

Figure 3b. Social Constructionism is aware that there are many viewpoints,

but they all belong to the same plane: it is still a Flatlanders' world

The third problem, related to the two previous points, is that constructionism and qualitative methods as used till now are still exceedingly unlikely to produce any really new knowledge in the psychological field. The reason is that these qualitative methods, even at their very best, cannot go beyond what the referents have to tell about themselves. In other words, at their best they can without distortion report on what sensitive members of the public already know about themselves, but they cannot go much further than that. For almost all purposes this is far better than mass-scale “quantitative research”, which by its insistence on looking at the averages of large populations is -- in a most literal sense – doomed to mediocrity. But still, it does not rise beyond what intelligent lay people already know. In short, 100 years after psychology fell into the abysses of radical and methodological behaviourism, it has finally, and with tremendous effort, climbed back to normal. The real climb has still to start.

Psychoanalysis

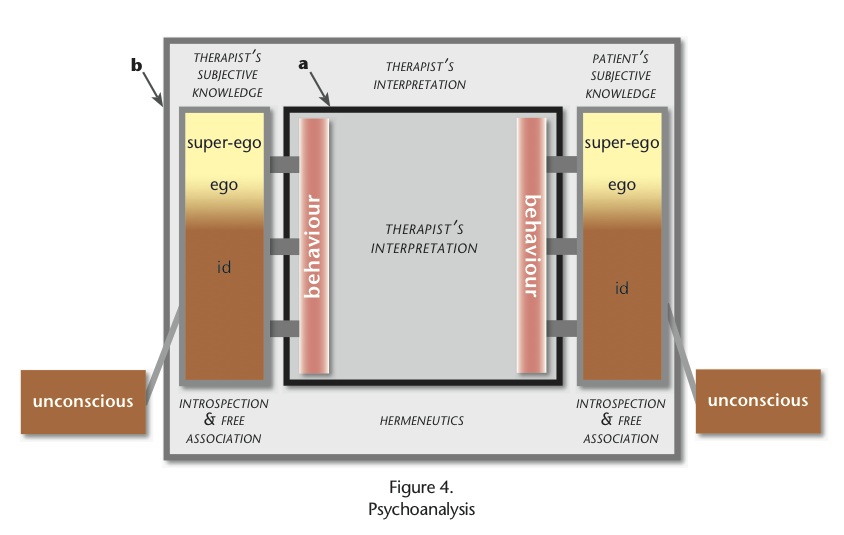

Psychoanalysis, starting off at roughly the same time as behaviourism, was the first major school of psychology to question the self-sufficiency of what is available to us in the ordinary waking consciousness. In the famous metaphor of the iceberg, Freud argued that most of what happens in our mind is happening below the surface and not immediately accessible to our surface awareness. He also realised that the therapist has to undergo his own therapy before he can safely help his patients, leading, long before the constructionists, to a somewhat symmetric diagram of the knowable universe.

All this is to the good, and yet, again, it is not good enough. From the standpoint of Indian psychology, it begins in the right direction, but then ends up in a perhaps even more serious quagmire than behaviourism. From an Indian psychology perspective there are three main difficulties with classical psychoanalysis: Its knowledge of the terrain outside the OWC is almost unbelievably limited – containing in fact not more than one exceedingly dark little corner; it has no convincing method to make its interpretations reliable and trustworthy; and it generalises, like behaviourism, the little knowledge it has, way beyond its legitimate limits. The core of the three is the second, the lack of an effective and reliable method to explore the territory outside the OWC. We'll now see what the Indian tradition can tell us in this area.

PART II: THE FOUR KNOWLEDGE REALMS THAT ARE NEEDED FOR A COMPREHENSIVE UNDERSTANDING OF HUMAN NATURE

Sri Aurobindo's four types of knowledge and how they can be perfected

Before we can begin to explore some of the additional inner realities the Indian tradition can open up to us, it may be useful to consider a distinction that Sri Aurobindo makes at one place6 between four different types of knowledge that all occur in our surface awareness.

- The first, and original one, is hardly used in ordinary life, and almost forgotten in modern philosophy of science, even though the case for its existence is convincing enough7. Sri Aurobindo calls it “knowledge by identity”, and it is the knowledge inherent in being. All we know of it in our naïve, surface awareness, is the simple fact of our own existence. Besides this, it is supposed to be the ultimate origin of the intuitive knowledge we have about the fundamental rules of logic and reasoning. In the Indian tradition it is called the dynamic truth-consciousness, ritam chit, which makes things what they are.

- The second type is “knowledge by intimate direct contact”. It comes to the fore in direct, pre-reflexive experiential knowing, as in our awareness of our own thinking or feeling.

- The third is used in introspection, where one looks at oneself in a semi-objective fashion. Sri Aurobindo calls it “separative direct knowledge”: separative because one distances one's self from what one observes, and direct because it does not need the outer, physical senses.8

- The fourth is our ordinary sense-based knowledge of the physical world, fully “separative and indirect": here one experiences oneself as entirely separate from what one observes, and one knows indirectly, by means of the physical senses.

For our ordinary, surface life, the division may not be so interesting, as these four modes of knowing generally occur together, but for the development of psychology the distinction between them is crucial. The reason for this is that science has mastered type four, “objective knowledge”, with stunning success, but has failed completely to move ahead with the other three. Early attempts to use type three in introspection failed, as it turned out to be too difficult to make introspection reliable. As far as type two is used (in therapy and skill-training) it is limited to its most simple and superficial manifestations. Of type one, we have only used one derivation successfully, and that is mathematics and the basic intuitive insight that underlies much of scientific development. Yet it is type three, type two, and a more complete version of type one, that we need if we want to take psychology ahead. The Indian tradition has put a tremendous effort into perfecting all three, and it is this that makes it so valuable for the further development of psychology.

Science has perfected type four to a remarkable degree. To understand the Indian attempts at perfecting the other three, we need to understand the role of yoga9 in the Indian tradition. Yoga is not only an effort to overcome suffering and reach a permanent state of happiness, bliss, but also, and perhaps even primarily, an effort to overcome ignorance and attain true knowledge. An extremely simplified form of the first of these two efforts, the pursuit of happiness, is already used extensively in applied psychology as “mindfulness”. What we suggest here is that we should also use the second half, the pursuit of knowledge, this time for the development of the theoretical foundation of psychology.

The processes and "inner gestures" yoga uses are complex and immensely varied in their appearance, but there seems to be one essential movement which permeates all the different forms yoga can take, and that is that yoga advocates for both happiness and reliable knowledge a peculiar type of inner detachment, a standing back from our habitual involvement in the workings of our mind, and with this, a release from our ego. Within the more limited context of knowledge gathering in the field of psychology, one could say that as long as we are obsessed with the defence of our existence as one small creature in a large and dangerous world, we have vested interests, and so we cannot judge freely. Interestingly, mainstream science has accepted this in the study of physical nature as the need for objectivity, for “a view from nowhere”, but it has not pursued it sufficiently for subjective, inner enquiry where one has to take one further step backwards. For the physical sciences it is sufficient to draw back from one's first impressions and habitual thoughts into an area of purer, more disciplined thinking. For psychology one has to draw back further, stand back from one's own thinking, feeling and sensing altogether, and watch one's own inner movements from an entirely pure, uninvolved consciousness. Strangely, it appears that this possibility has simply not arisen in the Western mind (or to the extent it has, it has clearly not been commonly accepted). At least since Descartes, there has been a for psychology disastrous conflation of consciousness with its content, a mix-up of consciousness with the mental processes that take place within it. The ancient Indian rishis found that it is possible, though not necessarily easy, to separate the two, and to fix one's consciousness in a position from where it can observe the workings of one's mind with complete impartiality. They realized that to increase one's psychological insight, it is not sufficient to get rid of one's preoccupation with self-assertion and self-defence, but that one should withdraw one's consciousness entirely from its involvement in one's thoughts, feelings and sensations. The interesting thing is that they found that this can actually be done, and that one's consciousness does not diminish in the process, but that it actually increases in clarity, intensity, sharpness, happiness, and even power. In other words, they found that from that completely detached, silent, and inherently safe inner position, one can study one's own inner movements with far higher levels of precision and detail than is possible through ordinary introspection, and that one can learn to modify the workings of one's mind and heart in ways that are completely inconceivable from the ordinary waking states of consciousness.

As may be clear, there are at this point several complications, side-tracks and implications one could and probably should get into. We are talking after all about a whole science, which developed over thousands of years and which in all its subtleties and ramifications is perhaps not less complicated and extensive than modern physics. To do so is however not the intent of this article, but there are a few points that deserve mention even in this short outline.

The first source of confusion is that the words "consciousness" and "mind" are used in such entirely different ways. In mainstream psychological thought, the word mind tends to be used for virtually everything that happens in the human psyche, not only thoughts but also feelings, sensations, intentions etc. The word consciousness, on the other hand, tends to be used only for the subjective awareness of these mental processes. As we are normally aware of only a small fragment of "everything that goes on inside our head", consciousness covers thus a much smaller set of phenomena than mind. In Indian thought it is the other way around, and consciousness is by far the wider term of the two. Though philosophers have conceptualized things in different, even diametrically opposite ways, the Indian tradition as a whole has still as its starting point that in the end everything in existence (sat) is in some way or another the manifestation of consciousness (cit), of something (tat) or someone (purushottama, Brahma, etc., etc.) that is in a completely absolute sense conscious and the expression of delight (ananda). Mind (manas) is in the Indian tradition just one "type of consciousness", or in another way of conceptualizing things, one peculiar working of universal nature that occurs in man and that lends itself to consciousness. Either way, mind is thus a much smaller term than consciousness.

The second point, related to the first, is that in mainstream psychology it is taken for granted that consciousness is produced, or, as it is said, “emerges” from the workings of the brain. The justification given for this belief is that if the brain gets disturbed, whether chemically or mechanically, consciousness seems to change or even disappear. The Indian tradition has, however, a very different explanation for this observation. It holds that our consciousness is in itself eternal and incorruptible, and that the only thing that happens when the brain gets disturbed or damaged, is that our consciousness can no longer express itself through this brain in its habitual manner, and that, if the damage is too much, it completely withdraws. The difference between these two fundamentally different ways of looking at the world is not small, and it is definitely not a simple matter of chicken and egg. If matter is first, then consciousness is a hard to explain "epiphenomenon", and all the deeper, inner experiences people have had over the ages should be considered subjective illusions. If, on the other hand, consciousness is first, then one can still explain the physical world as a niche within the wider framework of conscious existence and one can understand and develop a wide range of psychological phenomena, powers and possibilities that are presently considered “anomalous” and outside the ambit of science.

The third is, that disentangling one's consciousness from the egocentric activities of the mind/brain complex is not simple. There are innumerable pitfalls and complications. The good news is, however, that progress is possible, and that the path becomes more and more satisfactory and beautiful as one moves on.

Finally, it might be helpful if psychology got a little less preoccupied with attempts at imitating physics, and if it looked a little more attentively -- and this is the last time I mention it -- to astronomy. The reason is, that science does not only progress by doing experiments and checking results. It also progresses by perfecting its instruments of observation. And in psychology the obvious "instrument of choice" is our own human nature. My suggestion here is that the most effective way forward in psychology might well be an increasing attention for methods to hone our own inner nature as a kind of psychological observatory, a perfected inner “instrument of knowledge”, antahkarana.

To end this section, I’d like to come back to the four types of knowledge we started with. All these types of knowledge are in our unregenerate common nature far from perfect, but they can be perfected and can then be summarised as in table 1.

| type of knowledge | naïve mode | rigorous, expert mode | |

| 4 | separative indirect knowledge | ordinary, sense-based knowledge of physical world |

science |

| 3 | separative direct knowledge | introspection | pure witness consciousness (sakshi); purusha-based self-observation |

| 2 | knowledge by intimate direct contact | superficial experiential knowledge | pure consciousness directly touching other consciousness |

| 1 | knowledge by identity | superficial awareness of own existence | true intuition |

Table 1. Four types of knowledge: naive and perfected forms

- Separative indirect knowledge. The expert mode of the fourth type of knowledge is science, and modernity is making stunning progress in this area. As separative indirect knowledge is the sense-based knowledge of the world outside of us, it is eminently suitable for studying the physical world, but it is not the best way to study psychological phenomena.

- Separative direct knowledge. In the third type, mainstream psychology failed badly because the introspection-based schools tried to improve introspection without standing back far enough: the observing consciousness did not stand back from the processes it tried to study but remained involved in them. In other words, in ordinary introspection one part of the mind watches other parts of the mind, and as a result the problems of bias, vested interest, and infinite regress remain unresolved. The Indian solution is more radical. It suggests withdrawing the consciousness entirely from its involvement in mental processes and watching what happens in one's mind from a completely detached “witness” consciousness. The details of this process are obviously complex, both theoretically and practically, and they deserve more extensive treatment than can be given here but there is one easy to notice difference between the two approaches to self-observation that deserves to be mentioned: In ordinary introspection, there is almost always a part of the mind that provides a running commentary, judging, approving, disapproving, comparing, associating, what not. In detached self-observation, there is nothing of the sort; there is only a completely silent, non-judgmental, completely relaxed yet sharply focused attention. It is, as the old texts say, the difference between a windswept, muddy stream, in which one can see nothing, and a silent, crystal clear pond, in which one cannot only see the reflection of the individual leaves of the trees on the other side, but also the pebbles on the bottom.

- Knowledge by intimate direct contact. Interestingly, this detached observation seems to allow not only thorough knowledge of type three, unbiased access to one's own mind, but also to what happens in others and even in things. The logic behind this is that consciousness is ultimately one and that the world is not only interconnected in the outer physical world, but even more so inwardly, on the more subtle inner planes of thoughts and feelings. In our ordinary waking state our consciousness is entirely wrapped up in the working of our own nervous system, but once it is freed from there, it can in principle contact anything it concentrates upon. This opens a door to the whole complex world of parapsychological phenomena, which present day Western science has to label “anomalous” because they do not fit in its far too narrow, physicalist world view. If we accept the Indian consciousness-based means of developing psychological knowledge, an enormous world of “paranormal” psychological capacities & powers might open up to us.

- Knowledge by identity. In principle a further inner clarity should also open up a way to develop the first type of knowledge, knowledge by identity, which should enable a much more extensive use of intuition. The idea behind this even bolder claim is that the world is a manifestation of consciousness; that the original consciousness that manifested the world out of itself did so according to fundamental real-ideas (from the world of ritam chit), and that as we free our consciousness from its involvement in the small creature we think we are, it can identify itself instead with that original, creative consciousness and thus know everything the way the Divine knows it, from the inside. We can leave most of this safely for a remote future, though one could look at the stunning progress humanity has made in recent years in the physical sciences as a sudden influx of knowledge of this first type into our collective mind.

The four knowledge realms

Once we recognize how much the naive and expert modes of these four types of knowledge differ from each other, it becomes clear that there are actually eight clearly distinct forms of knowing that give access to eight different aspects of reality. For psychology it is practical to order these eight methods of knowing on a trajectory that reaches from the purely physical outer reality (studied by objective science) to the deepest innermost self (studied by yoga). Doing so, we can then group the aspects of reality these eight methods of knowing allow us to explore, into four distinct "knowledge realms": objective knowledge, subjective knowledge, inner knowledge and self-knowledge. Only the first two, objective knowledge and subjective knowledge, can be accessed with some confidence in the ordinary waking consciousness (OWC). Normally only an extremely limited, vague and often confused sense of the deeper realms of inner knowledge and self-knowledge can be obtained while one is in the OWC. For a complete understanding of human nature a detailed and accurate knowledge of these realms is however essential, and getting access to them tends to require considerable "inner work". In the Indian tradition this inner work is often referred to as "yoga" and n the following text we'll use the word "yoga" in this broad and general sense (without implying in any way that that it would not be possible to explore these two realms through other methods). Table 2 presents an overview of the four knowledge realms that are needed for a complete psychological understanding. It shows how the naive and expert modes of Sri Aurobindo's four knowledge types work themselves out into eight forms of knowing that can be used to explore eight different aspects of reality:

| knowledge realm | usage | knowledge mode & type (acc. to Sri Aurobindo) |

known reality | |

| objective knowledge | A. ordinary,

sense-based knowing |

naïve separative,

indirect knowledge (4) |

physical world | O W C |

| B. objective science | expert separative,

indirect knowledge (4) |

|||

| subjective knowledge | C. introspection | naïve separative,

direct knowledge (3) |

outer nature | |

| D. superficial experience | naïve knowledge by

intimate, direct contact (2) |

|||

| E. superficial awareness

of own existence |

naïve knowledge

by identity (1) |

surface self | ||

| inner knowledge | F. witness consciousness

(sakshibhava); purusha-based self-observation |

expert separative,

direct knowledge (3) |

inner nature | Y O G A |

| G. consciousness directly

touching other consciousness |

expert knowledge by

intimate, direct contact (2) |

|||

| Self-knowledge | H. truth-consciousness,

gnosis, intuition |

expert knowledge

by identity (1) |

true Self,

Real-Ideas |

Table 2. The four knowledge realms needed in psychology

The four "knowledge realms" indicated in Table 2 can then be described as follows:

- Objective knowledge. This is the knowledge we have of the physical and socio-economic world around us. It is sense-based and (supposed to be) guided by reason and “common sense”. There are two varieties of it. The naive variety is simply whatever ordinary people know about the world outside of themselves. The expert variety is science. These two don't differ in principle, but they differ considerably in their actual processes and results. Science is more rigorous, specialised and cumulative; the senses are extended by instruments that have been constructed with the help off knowledge of this same type; the reason is extended in the form of mathematics. Modernity is the scene of an almost incredible collective growth of this type of knowledge.

- Subjective knowledge. Subjective knowledge is the knowledge we have of what is happening inside ourselves. The word “subjective” has nowadays largely negative connotations, and I use it here only for the naive variety of what we know about our own nature and our own self-existence. Within the realm of subjective knowledge one can distinguish three types: introspection which is a naive attempt at being “objective” about oneself (knowledge of type three), experiential knowledge which deals with processes we intimately identify with (knowledge of type two), and a superficial, ego-based awareness of one's own identity. All three are limited in scope and “subjective knowledge” has access only to a tiny fraction of what we are and what happens inside ourselves.

- Inner knowledge. This consists of the sophisticated, expert variety of two types of knowledge of which subjective knowledge uses the naive variety. Expert knowledge of Sri Aurobindo's type three is the pure, detached witness consciousness that allows genuinely “objective” knowledge of whatever happens in one's own inner nature. The expert variety of type two, knowledge by intimate direct contact, allows one's consciousness to touch directly the consciousness in others and even in things so that one can know these by an intimate, unmediated direct contact.

- Self-knowledge. This is the expert variety of knowledge by identity (type one) and it leads us directly to who we are in the very essence of our being. The little of real self-knowledge that reaches our surface consciousness may never attain to that level of perfection, but in itself this type of knowledge is intrinsically true and perfect. It is the secret origin of whatever there is of real truth in all other types of knowledge. According to the Indian tradition, a perfect knowledge of oneself automatically gives in principle the possibility of perfect knowledge of everything else.

As mentioned before, the realms of objective and subjective knowledge (as defined here) are the only ones that can be accessed fully in the ordinary waking consciousness (or OWC). Because we have made such tremendous progress with the expert variety of objective knowledge (at least in the physical domain), we tend to rely on it almost exclusively for our public affairs. Only where this type of knowledge can clearly not provide the answers, for example on issues that demand a value judgment, we respect subjective knowledge. The mainstream culture tends to doubt and distrust all forms of inner knowledge and what we have here called "self-knowledge", deriding them as "essentialist". The reason for this seems to be that the little we know about these inner realms tends to be encrusted in religious rituals and dogmas and in all kind of non-self-critical experiments and beliefs at the margin of the global civilization. As a result of all this, the little we know from here impresses the scientific mind as an intractable mixture of partial truths and total confusion that should perhaps be tolerated in people's private lives, but that has no place in public life or the hallowed halls of science. To get high quality inner knowledge and self-knowledge, full inner control over a whole range of different types of consciousness and a considerable amount of inner discipline are required, and for this the West has no established method. Mystics and other exceptional individuals have of course managed this in all times and cultures, but the Indian tradition has specialised in it, and it has developed an enormous amount of detailed know-how. In this article I contend that a serious practice of some form of jnana-yoga (yoga of knowledge) is likely to offer one of the most efficient ways to develop a more comprehensive psychological understanding. To substantiate this contention, I will now indicate (again in a very short and schematic fashion) which aspects of reality the Indian yoga- and consciousness-based approach to psychology could open up to us. To this end I've indicated in the next two sections in some more detail which aspects of reality are knowable in each of the four knowledge realms.10

PART III: An approach to Psychology with roots in the Indian tradition

Introduction

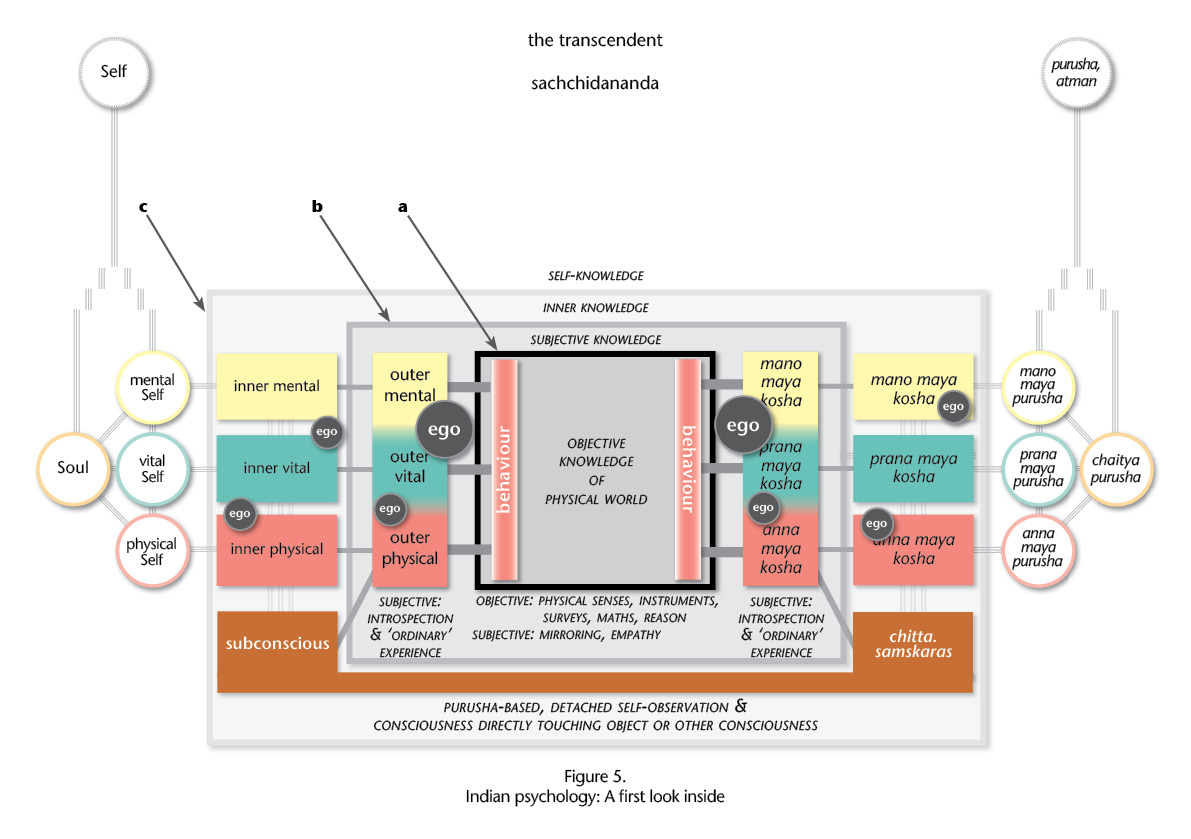

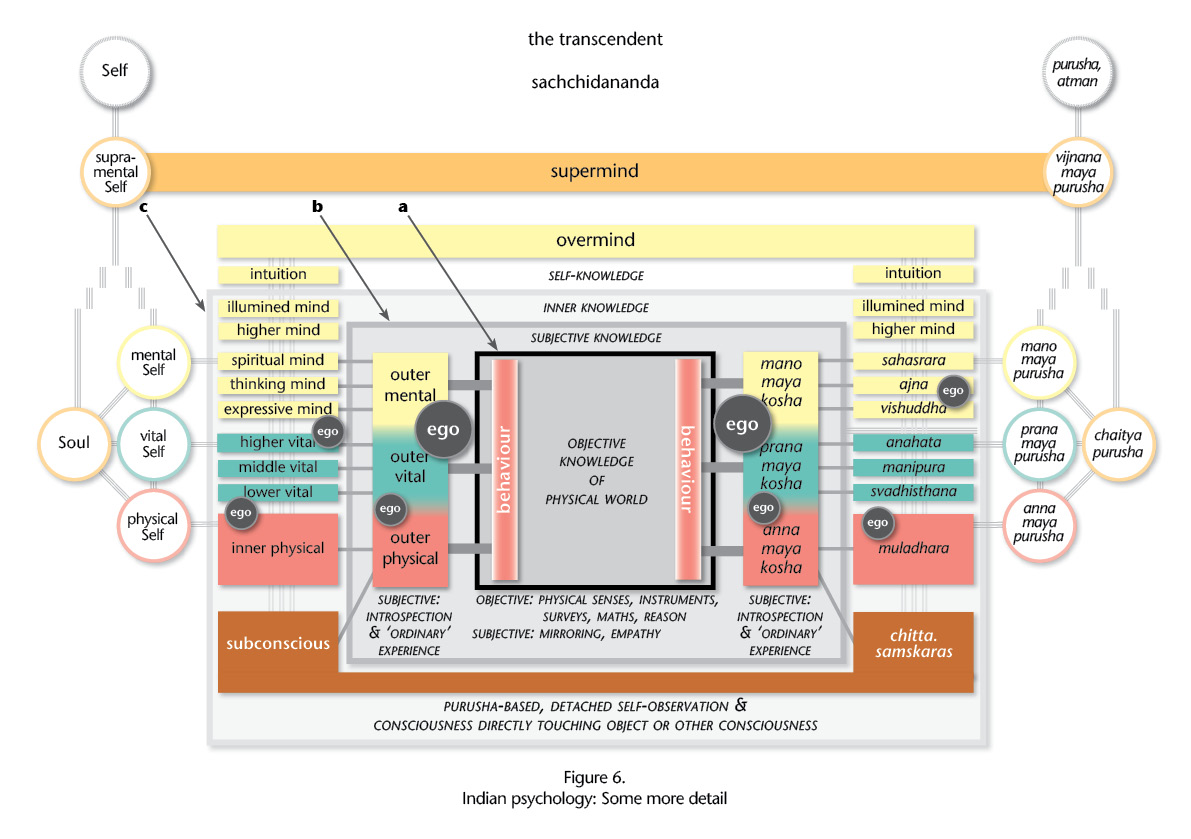

For the following exposition I've again made use of the work of Sri Aurobindo. The two diagrams in this section have the same basic structure; the only difference is that the first one is even more simplified than the second one: it depicts only what can become clear (and is useful to know) during “a first look inside”. The diagram in the next section has some more detail.

As may be clear, the Indian psychology perspective contains many new elements, but before we can explain the details of the diagram and content of the four knowledge realms, there are a few more general observations to make.

The basic layout of these diagrams reflect that humans are rarely fully “alone”: we tend to spend our time in all kind of relationships. These relationships are not necessarily with one other person, they can also be with a group of people, a task, a thought, an element of the physical reality, they can even be with ourselves or the Divine. Fully alone we rarely are. Because of this, the common pictorial descriptions of human nature always feel a bit artificial and incomplete, and so, in these diagrams I have depicted the different parts of the being of one person in relation to those of another person. One could of course also see them in continuation of the constructionist's universe with the researcher on the left and the subject on the right, but the basic layout applies equally to two “ordinary” individuals as to a researcher and his subject.

Another thing to notice about these last two diagrams is, that they may appear to be inverted: the more superficial, “outer” regions of our psychological reality are depicted in the centre, while our inner realities are towards the periphery. The reason for this apparent inversion is that the diagrams depict two “half people": they depict a horizontal trajectory from one person's innermost Self at the extreme left, via his inner and outer nature, into the public physical space where behaviour takes place, and then from there, via the outer and the inner nature of the other, to the innermost Self of the other on the far right. A helpful side effect of the inversion is that it harmonizes with the peculiar fact of experience that as one “goes inside", one actually enters larger and larger realities. The “inner realities” are experienced as wider, more open than the physical outer world, and the further one goes “inside” the wider one's world becomes. In fact, the more one becomes aware of the inner worlds, the more it looks as if the entire physical universe exists only within a small corner of these inner worlds.

The diagrams as a whole give the impression that the whole wide world hangs down from two little balloons that represent our ultimate Selves, and this is perhaps as it should be: In the Indian tradition the Self is the primary reality, the essence on which all the rest depends. Finally it may be noted that, although one is rarely aware of this when one is in the limited physical consciousness, the more subtle “inner” types of knowledge (Sri Aurobindo's type one and two) do influence and penetrate the more superficial “outer” types of knowledge (type three and four).

As we human beings tend to live initially quite close to the surface of our nature, we'll describe the diagram from our outer behaviour in the central square — which depicts the physical reality — via our outer and inner nature, to our innermost Self on the left of the diagram. On the left of the diagram I've used Sri Aurobindo's English terminology; where appropriate, I've given on the right the Sanskrit equivalents. The four knowledge-realms that together cover our psychological reality are indicated in this diagram as grey rectangles. The inner three have borders in darker shades of grey; the realm of the Self has, perhaps significantly, no outer limit.

A first look inside

Objective knowledge

Objective knowledge is knowledge of type four: it is separative and indirect, and it is the most superficial type of knowledge. It consists of what we become aware of, through our senses, in the outer, physical world. In our ordinary daily life, we use a naïve, untrained form of it, while Science is its most sophisticated development. In modern times, it is this type of knowledge we trust most, possibly because it provides us with power over the physical world, and through that, with power over others. It is, moreover, the source of all our technological gadgets and comforts. In yoga it is considered the lowest type of knowledge, the epitome of avidya, ignorance. The reason for this low valuation is that it is right on the surface, and least connected with our soul. The world of objective knowledge contains our behaviour. As the behaviourists slowly discovered, human behaviour has an extremely complex causation, and so as long as one's knowledge is limited to objective knowledge, only some limited aspects of it can be reliably predicted, and that too, only in a broad, statistical sense. To really understand individuals one has to know what happens deeper inside.

Line a separates the world of publicly observable behaviour that can be known through objective knowledge, from the parts of our nature that are, at least in first instance, only available to the individual as subjective knowledge.

Subjective knowledge

Subjective knowledge consists of naive, untrained forms of type three and type two, introspection and simple, naïve experience. It gives us all that we know about ourselves in the ordinary waking consciousness. It is all that mainstream psychology deals with. From an Indian psychology standpoint, it is not worth much, and is often described as a source of typical beginners' errors (e.g. Chandogya Upanishad 8.7-12).

The realm of subjective knowledge contains an area that in our diagram has the labels, outer mental, outer vital, and outer physical. In mainstream psychology this area might have been called “inner” as it cannot be seen on the outside of the body, but from an Indian standpoint it is so close to the surface that it deserves to be called “outer”. In this outer realm, the division between mental, vital and physical may not immediately be clear as on the surface of our nature they are always mixed together. In emotions, for example, there is a physical component as emotions typically affect one's pulse rate and blood pressure; there is a vital component of feelings and assertiveness; and there is a mental component as the emotions come packed in words and thoughts. In the diagram, we have indicated this mixed character by making the borders between these three layers fuzzy. As a result, the justification for the simpler Western division between mind and body seems in our outer nature more obvious: the body is the physical stuff you can touch and see, while the mind is everything else, and the body–mind division can be compared to the easy to understand division between hardware and software.

The Indian division in three major categories is based on a more subtle observation, which gets its full justification only in the “inner” and “true” parts of our nature. The terms mental, vital and physical are rendering the Sanskrit concepts of manas, prana and annam. In the inner being these three principles are experienced as three essentially different types of conscious existence. They are seen as so essentially different and as so completely independent of each other that they are sometimes described as three worlds, three planes, or three births, and in case of the individual organism, as three sheaths. The division between the mental and the vital plane comes out most clearly in the clear difference between the svadharma, the basic law of right action, of these two planes. The mental is into thought, and it is naturally inclined to seek for, and to express truth. The vital on the other hand, is into feelings, into likes and dislikes, exchanges of various kinds, and it pursues self-assertion, enjoyment and possession. In the mind, understanding has the greatest value, just as self-assertion is the basic objective in the world of the vital. A modern way to look at it is to say that the vital comes from an earlier stage of evolution when survival and happiness were the main issues that determined our actions. Now, in us mental beings, the vital should not any longer decide what we do, but provide energy for whatever is decided by the later-developed and higher-order centre of consciousness, the mind. Once our consciousness has emancipated sufficiently out of the biologically determined centres of our being, we can leave the decision taking process to the inmost individual centre of tconsciousness, the soul, the psychic being.

It may be noted that even though each layer has elements of all three gunas (qualities), the typical guna of the mind is sattva (harmony), of the vital, rajas (energy), and of the physical tamas (inertia).

A major element of the outer being is the ego. The Ego is in Sri Aurobindo's view a temporary, provisionally constructed centre that serves as a coordinating hub for the activities of the nature, needed as long as the real Self and the Soul are not fully known and made dynamic. It may be noted that the diagram contains several smaller egos, both in the outer and in the inner nature. These are subsidiary egos that can be located anywhere in one's nature and they assume a character according to the part of one's nature they occur in. A typical example might be someone who is generous and flexible in his vital nature, inclined to adjust and share his possessions with others, but egoistic in his mind: proud of his ideas, insisting that others change theirs and acknowledge his superiority. Though necessary in the early stages of one’s individualization, all the functions of the ego(s) can be taken over by the Soul or Psychic Being which we will discuss later.

Line b is the borderline between the realms of subjective and inner knowledge.

Inner knowledge

Inner knowledge, once developed properly, consists of more sophisticated forms of knowledge of type three and two.11 Sri Aurobindo calls the realm that inner knowledge deals with subliminal because it is below the threshold of our ordinary waking consciousness (or OWC). This subliminal or “inner being” is the part of our nature that is the closest to our true Self, and it is the first to accept its beneficial influence. It is, however, still a mixed realm, and we can find here things that are higher, nobler and further evolved, as well as things that are lower and more primitive than what we find in the OWC.

Whether our surface being is conscious of it or not, what happens in the subliminal has a profound and pervasive influence on all we do, feel and think, and so its exploration and purification are crucial for our individual well-being as well as for the development of psychology. It is normally not accessible in our OWC, or through ordinary introspection, but many people have glimpses from it in their dreams. In Psychoanalysis it is accessed through “free association”, and in some other forms of Western psychotherapy through hypnosis. In both methods it is exceedingly difficult to distinguish perception from imagination and truth from falsehood, and one has to rely on somewhat arbitrary—and often contradictory—systems of interpretation. In Indian psychology, the deeper layers of human nature can be studied with much greater precision and reliability by means of the pure witness consciousness. As discussed above, of the four types of knowledge, the second type, separative direct knowledge, and the third type, knowledge by direct intimate contact can be perfected through contact with the mental Self or manomaya purusha.

The lowest, most primitive part of the subliminal, where we store the stuff we do not want to see, is what Freud called the “unconscious”. We call it here the “subconscious” as in the Indian view it is not entirely without consciousness, but only characterized by a very low, primitive type of consciousness.12 It is from this subconscious realm that the poisons arise during the churning of the ocean in the Puranic story.

In this diagram, the subconscious has stretched downward and is now connected with the subconscious of “the other”. It has been depicted this way to indicate two interesting phenomena. The first is, that as one's consciousness grows and rises, one also sees more clearly into the depths. It is as if the increasing inner clarity lights up more and more dark corners in one's nature. The second is, that one's subconscious is not entirely personal: we are all connected. This is true for all layers, but in the subconscious it is perhaps the most prominent and definitely the most troublesome: To arrive at peace and harmony, one has to clean up not only one's own past confusions, but, at least to some extent, even those of others.

In analogy with the subconscious, Sri Aurobindo sometimes calls the higher regions of the inner being the superconscious, but this part of the nature we'll discuss in the next section. The inner being is also the realm where we are in direct contact with other beings and a wide variety of occult, cosmic powers.

Immediately above the subconscious we have the inner physical, inner vital, and inner mental. These three layers are here fully separated and coloured differently as in the inner nature each plane can actually be experienced in its unique, distinct, flavour. Emotions, for example, can in the inner nature be experienced as pure energy, and feelings need not be rendered into words and may be unconnected with the body.

As mentioned in our discussion of the subconscious, the inner mental, vital and physical are not purely individual: at this level we are all directly connected with each other. As a result, we can, within the realm of inner knowledge, know each other through knowledge of type 3. It is held, in fact, that the reason we normally do not know each other directly, from the inside out, is not because we are separated from each other: we are not. The reason is that within ourselves, there is a wall between our outer being, which relies on objective and subjective knowledge, and our own inner being in the subliminal realm that can only be known through inner knowledge. In other words, as we get to know our own inner being better, we find that more and more often we begin to understand others as well, in what seems to be an entirely direct, non-mediated, non-constructed way.

Line c in the diagram separates prakriti, Nature, from purusha, the Self. The Self is the carrier of one's consciousness and the centre from where one is aware of everything. It is worth noting that in the Samkhya philosophy, which Patanjali follows in his Yogasutras, everything that can be made an object of observation — even thoughts and feelings — belongs to (universal) Nature, and only the pure, silent, witnessing and supporting consciousness belongs to the Self. In the later dualistic philosophy of Samkhya, this line of demarcation is seen as absolute: purusha is pure consciousness, and prakriti is entirely unconscious. In the older more flexible Samkhya of the Bhagavad Gita, in Vedanta, and especially in the Tantric writings of Abhinavagupta, it is stressed that in the end all is One, and as such, nothing can be entirely unconscious: prakriti is moved by a personalised and conscious female force, Shakti, which is initiated, sanctioned, supported, ruled and inhabited by the consciousness of the Ishvara, her Lord.

Line c also divides the realms known through objective, subjective, and inner knowledge, which are all at least to some extent constructed, from the realm of knowledge by identity, which is direct and inherent.

Self-knowledge

Self-knowledge, which is a knowledge by identity, tends to become manifest first in one of the three embodied centres of consciousness, the mental, vital and physical Self, which preside over one’s individual existence in the three major planes of existence, the manomaya, pranamaya and annamaya kosha. The Self of the mental plane (the manomaya purusha) deals with knowledge; the Self in the vital plane (the pranamaya purusha) is the centre and supporter of exchange, possession, energy and enjoyment; the physical Self simply is, and supports the body.

For psychology as a science, the mental Self is perhaps the most interesting as it is the seat of the sakshi, the pure witness consciousness which allows a completely unbiased sharp perception of everything that happens in our individual nature. The vital Self is characterised by an undisturbed and seemingly unlimited joy and energy and has as such its own role to play, but it is perhaps most known for the fact that it is so often mistaken for the soul. The physical Self is well-known to athletes at moments when they “enter the flow” and their body consciousness handles everything fully on its own without any interference from the mind or vital.13

While the Self is the carrier of the ultimate svabhava and svadharma of the individual, the soul may choose to express only a subset of this svabhava during one particular birth. An example may make this clearer. If it is part of a subsequent destiny of an individual to express subtle, inner realities in the form of poetry, it could choose first for a life as painter, as this would enable it to develop the capacity to hold things up to the mind’s inner eye with subtlety and detail. In a subsequent life it could retain this inner ability of detailed visualisation, while suppressing its capability to paint, exposing itself instead to wide variety of literary expression. Through this particular combination of supporting and limiting influences, it could then develop the capacity to express rich inner visualisations through the medium of poetry.

The Soul is the very centre of the embodied individual, and as such a representative presence of the ultimate, immutable Self beyond time and space. In the beginning of one's individual evolution, Sri Aurobindo describes it as no more than a “psychic entity”, a spark of Divinity, but over many lives it gathers experience and so it forms around itself what he calls an evolving soul-personality or “psychic being”. The psychic being consists not only of the original spark or divine presence, but also of all those elements of the inner nature that have come permanently under its influence. The Sanskrit term that comes closest to what Sri Aurobindo calls the psychic being is chaitya purusha. Antaratman is another term used for the same centre of consciousness as it is found deep behind the heart, but most authors who use this term stress its eternal and immutable, rather than its evolving characteristics. Psychologically, this centre contains both: it is the immutable Self as it expresses itself in time. Once the soul takes over as the centre of the embodied individuality, there is according to Sri Aurobindo no longer need, or place, for the ego.

The ultimate Self or atman (in the diagram at the top left corner) is the absolute essence of the individual. Like the Divine, which we can in this context perhaps look at as the Self of the Universe, our ultimate identity exists simultaneously in the individual, the cosmic and transcendent aspects of reality. If the Divine is anantaguna, of infinite quality, the individual Self, being an inalienable and eternal portion of the Divine, has a subset of that infinity. It is this subset that determines the individual's svabhava and svadharma and they, in turn, determine the individual’s destiny, its role and position in the manifestation.

The reason that the lines connecting the Soul and mental Self with the Self above have been staggered like the Empire State Building is, that the Self tends to be experienced as vertically straight above each. One should not take any of this too serious though: the inner worlds are not dimensional in our ordinary physical sense, and the various Selves can also be experienced as concentric or in many entirely different relationships.

Sachchidananda (Existence, Consciousness, Bliss) in the centre at the top of the diagram is the traditional way to describe the nature of Brahman as the original source and essence of the manifestation. It reflects the psychological fact that if one manages to empty one's consciousness from all relative and temporary content in an aspiration to find the absolute essence of reality, one can experience overwhelming intensities of what feels like perfect, absolute, true being, consciousness and delight.

The term “transcendent” is traditionally used for that what goes beyond all manifestation. This and the processes and states leading to it have been given many names, all with slightly different meanings and connotations, e.g. sunya, nirvana, mukti, moksha, samadhi and so on. Psychologically, the concept of the transcendent is peculiar, because the transcendent is by definition entirely beyond the manifestation, while still, we can have at least subjectively the sense of entering into “it” and coming back from it. What is more, doing so is a life-changing event: it leaves one with a permanent certainty of having found the absolute, the ultimate, That, and with this, the certainty that ultimately all is well, and that all that happens “down here” in the manifestation can never take away anything of that ultimate perfection and supreme “wellness”. It is for this reason that both in yoga and in Buddhist practice so much importance is given to this “experience” (or rather “non-experience"?). For psychology it is important as it helps one to be detached and impartial in one's perceptions and actions.

It may be kept in mind that while there is an enormous variety in the ways different schools have described the relations between what we have here called our outer nature, our inner nature, our highest, innermost Self, the outer cosmic reality, and the Divine, it is not impossible to find the common core, even though one may not be able to describe it without choosing sides in some of the many quibbles about what describes it best. Fortunately, our consciousness is not limited to what can be known and expressed explicitly.

We'll now fill in some more detail in the inner and higher worlds.

Some more detail

Subdivisions in the vital and mental

The first thing one may notice when one compares the following diagram with the former, is that the inner vital and inner mental have each been divided into three sub-planes. This may seem a useless complication, but it does correspond to an influential aspect of our inner reality, and the sub-divisions are helpful if one wants to understand the source of contradictory feelings, thoughts and motives. The subdivisions of the vital and the mind correspond to the higher six chakras, whose Sanskrit names I've indicated in the diagram on the right. (I've not given Sanskrit words for the higher levels of consciousness as the Sanskrit words used to indicate these worlds have different meanings and connotations in different schools, so that the whole exposition would become far too complex for this introductory overview. Personally I've found Sri Aurobindo's divisions and terms eminently clear and practical.)

The chakras have been subject to much useless mystification and pseudo-spiritual sensationalism, but they refer to a set of experiences that occur sometimes spontaneously and that are fairly common amongst those who meditate or do yoga. Even the rising of the kundalini, the psychic energy, from the muladhara at the base of the spine to the sahasrara at the crown of the head does occur sometimes without any specific effort or training. Perhaps more importantly, the chakras relate to different types of consciousness that are fairly easily accessible to almost everyone. For some reason these different types of consciousness seem to be stacked up one above the other in our inner, subtle physical body, and there are clear references to the highest five in the English language.

When you read a difficult text

or think about some complex abstract problem, the centre of your awareness

tends to be located in the centre of your forehead. When you

stop reading and try instead to feel love or compassion, it shifts automatically

to your heart.

It is interesting to see if you can feel love or compassion

while looking at the world from some place behind your

forehead. Most people find this impossible: if you insist on the feeling of compassion,

it is as if you are pulled down to the middle of your chest. Similarly,

when you force yourself to stay in your heart while reading a difficult text,

you'll notice that the ideas don't register, they go, in a most literal sense, “over

your head” (or rather “over your heart”).

In martial arts and contact sports

like boxing, it is crucial to centre yourself in the centre of your body,

your hara, as otherwise it is too easy to push you over.

When one has difficulty controlling one's anger, it often helps

to splash some water over

one's face or walk around the block. This helps not only because it “cools

you down”, dissipates the energy, and forces a little break; it also forces

your consciousness into your physical being which in itself is not angry: the

anger is located in the vital part of the nature. Counting to ten helps for the

same reason: it forces you away from the vital, into the mind.

- The lowest chakra, at the bottom of the spine, is the muladhara, the seat of the kundalini energy, and the physical consciousness.

- Just above it, is the svadhisthana, the chakra of the lower vital consciousness where we find sexuality and the search for minor, personal comforts.

- Above that, we find the manipura, housing the middle vital with our larger ambitions for power and possession. This is the Hara of Japanese martial arts, and also the source of what businessmen call “gut-feelings”. Interestingly, “having guts” means being courageous and daring, qualities that occur when one's consciousness is powerfully present at this level.

- The anahata at the level of the heart, with the higher vital consciousness, carries the more sophisticated human emotions of love, compassion etc. If you want to encourage someone to be more generous or compassionate you don't say: “open your head”, you say, “open your heart”.

- Above the heart, at the level of the throat, comes the vishuddha in the lowest mental layer, the expressive mind. Its character depends on what it expresses: it can express vital feelings coming from below as well as thoughts and inspirations from above. It is not only concerned with verbal and vocal expressions, it is also active in other forms of expression.

- One further up is the ajna chakra, the thinking mind proper located behind the forehead. This is the location where philosophers and academics feel that their consciousness resides. Again, a child who needs to think more clearly is asked to use his head, not his heart, let alone his guts.

- The last chakra, the sahasrara at the crown of the head, houses the spiritual mind, and is for obvious reasons not much mentioned in the English language, though there may be a vague reference to it in the fact that highfalutin ideas are said to go “over one's head”. It is through here that inspirations are most often felt to enter.

Interestingly, the different layers are in English also used to indicate specific kinds of unease: there is a commonly understood difference between butterflies in one's stomach, a heartache, a lump in one's throat, and a headache.

Finally it may be noted that the gutsy(!), flowery language in which these various centres of consciousness are addressed in English suggests that though they are part of our common understanding of human nature, and though they have quite a prominent place in literature, they have not been given much attention in academics. This is unfortunate, because a clear understanding of these different centres can help considerably with the development of insight and mastery over one's drives and motives. The ability to locate the centre of one's consciousness in any of them at will should in fact be considered an important life-skill, which could quite well be taught in school. It appears that the idea that consciousness is generated in the brain has stood in the way of psychologist paying any attention to this otherwise interesting phenomenon.

There are other useful subdivisions of the vital and mind, and there are several subsidiary chakras in between the seven major ones given here, but they have not been mentioned here.

Planes above the ordinary mind

Above these layers of consciousness we all know, Sri Aurobindo distinguishes four more layers that still belong to the mental plane, but that most people have limited or no direct access to.14 The Higher mind, closest to the normal intellect, is a plane where ideas still take the form of thoughts, and are “clad” in words and sentences, though such thoughts are not any longer constructed in the ordinary way: they come, more or less ready-made from above. On this plane it is always immediately and intrinsically clear how different and seemingly contradictory thoughts hang together in a higher order synthesis. This is the plane where holistic and “integral”15 philosophers get their ideas. Above this plane we find the Illumined mind where ideas are not so much rendered in words as in luminous images. Truths seen on this plane tend to be, in a quite special way, luminous, convincing, subtle and precise, but difficult to render into language, which can from here look clumsy and artificial. Above these two, Sri Aurobindo positions Intuition, a plane of intrinsic truth, from where the lower levels get whatever core of truth they contain. Drops and glimpses falling from here into the ordinary mind are often called intuitions, but by the time our ordinary physical mind has rendered them, they are again at least partially “constructed” and as such prone to error.16 It may be noted that an ascent through these planes goes together with the sense of increasing intensities of light, truth and bliss. The highest mental level, the Overmind, has been described as a golden lid, and as an ocean of lightning of such blinding intensity, that one cannot see through it and discern what is beyond. The overmind is, moreover, completely cosmic in its nature, and to reach this level, every last trace of limited, egoïc individuality must be completely gone. And yet, as Sri Aurobindo often says, there is a beyond.

It may be noted that line c, which divides purusha from prakriti, has not been shown beyond the level of the illumined mind. This is somewhat arbitrary, but not fully. The higher one rises in consciousness, the less absolute the division between purusha and prakriti becomes. While the distinction is perfectly clear and extremely useful for the practice of yoga at the level of the ordinary thinking mind, it has no real meaning any more on the level of the perfectly unitary supermind. The reason to end the line at this specific level between the illumined mind and intuition is, that in Sri Aurobindo's system, the type of knowledge that exists on the level of intuition is thoroughly of the fourth type, knowledge by identity, where there is no real division any more between knower and known, but at most some kind of potential, pragmatic distinction. In this sense, both intuition and overmind can thus be looked at as planes of true knowledge. Intuition is still predominantly individual; overmind is predominantly cosmic, though it still contains the special kind of “cosmic individuality” that is typical for the Gods. Shadows from the overmind onto the plane of the ordinary thinking mind are supposed to have created the major organised religions.

Supermind is an entirely non-mental plane of gnostic consciousness. It is the Maharloka of the Puranas, which separates the higher hemisphere of sachchidananda from the lower hemisphere of mind, vital and physical. As it is entirely above the mind, it cannot be apprehended from a mental consciousness, and it has been given scant recognition in the later philosophical systems. According to Sri Aurobindo, it contains three different types of knowledge, always operating at the same time: samjnana, prajnana and vijnana. Samjnana is solidly immerged in a sense of oneness; prajnana is still dominated by oneness but does apprehend differentiation; vijnana is also still rooted in oneness but the apprehension of differentiation is its main function (which might explain why the term gets later used in the much diminished sense of intellect). Real divisions are not yet there at the level of the supermind; they become possible only on the highest level of the mind, the overmind. On the level of the supermind, chit and tapas (consciousness and force) are also not yet distinct: knowledge is here still directly and inevitably creative and dynamic. While truth at its highest is satyam, truth of being, supermind is predominantly the layer of the dynamic truth, ritam chit, the truth that manifests, through “real ideas”, the order of the worlds. In short, supermind is a world where absolute oneness, truth and perfection go together with differentiation, creating a world of perfect harmony. Being entirely beyond the mental plane, perceptions of the physical world need not run through the sense-mind anymore, so even the physical reality as seen from here has an entirely different appearance. For several detailed descriptions, see Sri Aurobindo (2005). It may be noted that while the Supermind is frequently mentioned in the Puranas (as mahas) and in the Rig Veda (as the realm of Surya), it seems to have been forgotten in later texts. It looks as if people learned to jump straight from one of the higher levels of mind into the anandamaya kosha.

TO CONCLUDE

A few disclaimers

Before we conclude, some words of caution. First of all, all this is no more than a crude simplification. As mentioned in the beginning, none of the “things” on these diagrams are remotely like “things” in the simple dimensional, physical sense. It is, for example, true that the psychic can be found deep, deep inside, behind the heart, and one can feel there the presence of the Divine (or one's inner Guru), yet one can also feel entirely surrounded and invaded by the Divine or by one's Guru's presence. Similarly, one can feel one's Self as eternal and infinite, way above one's outer nature, but one can also experience it as thoroughly interwoven with it, and yet, within fraction of a second, one can equally sense the absolute absurdity of speaking of a “self” and experience the total emptiness of the very idea of it. The oppositions that have occupied and divided philosophers for millennia can in a higher, more subtle psychological experience be combined or juxtaposed as equally real without any difficulty or contradiction. Sri Aurobindo says of these dualities that from the standpoint of a higher consciousness, “they are so simply and inevitably the intrinsic nature of each other that even to think of them as contraries is an unimaginable violence” (The Synthesis of Yoga, p. 283).