What makes us what we are?

An overview of influences on our personality

Matthijs Cornelissen

last revision: 18 February 2024

Introduction

In this chapter we'll have a look at what influences our character and our life. We won't go into the fine detail of the specific influences that are active in each one of us individually — some of that will come in the chapters on self-development, education and therapy — but we will have a look at the main categories under which these influences can be grouped, because they belong to a few essentially different types. We'll look at these categories from the outside inwards, with the help of five diagrams:

- The first diagram shows what can, at least to some extent, be known in the ordinary waking consciousness.

- The second also includes what can be known once we begin to explore the "inner worlds".

- The third shows how reality looks when we have an experience or realisation of the Divine in one of its more transcendent aspects. There is then often a gap between the Divine and the world.1

- The fourth diagram shows how this gap can begin to be bridged, how we can become gradually more aware that the Divine and the world are actually one and that we too are both this and That, when we begin to see how That, the True, the Real can influence our life down here, first only deep inside and then very, very gradually even in our outer life.

- The fifth and last diagram depicts how Sri Aurobindo describes a future in which the centre of our consciousness is settled in our eternal Self and our nature is entirely transformed under its influence and all the functions of the ego have been taken over by what he calls our psychic being.

We will now have a closer look at these five "levels of determination".

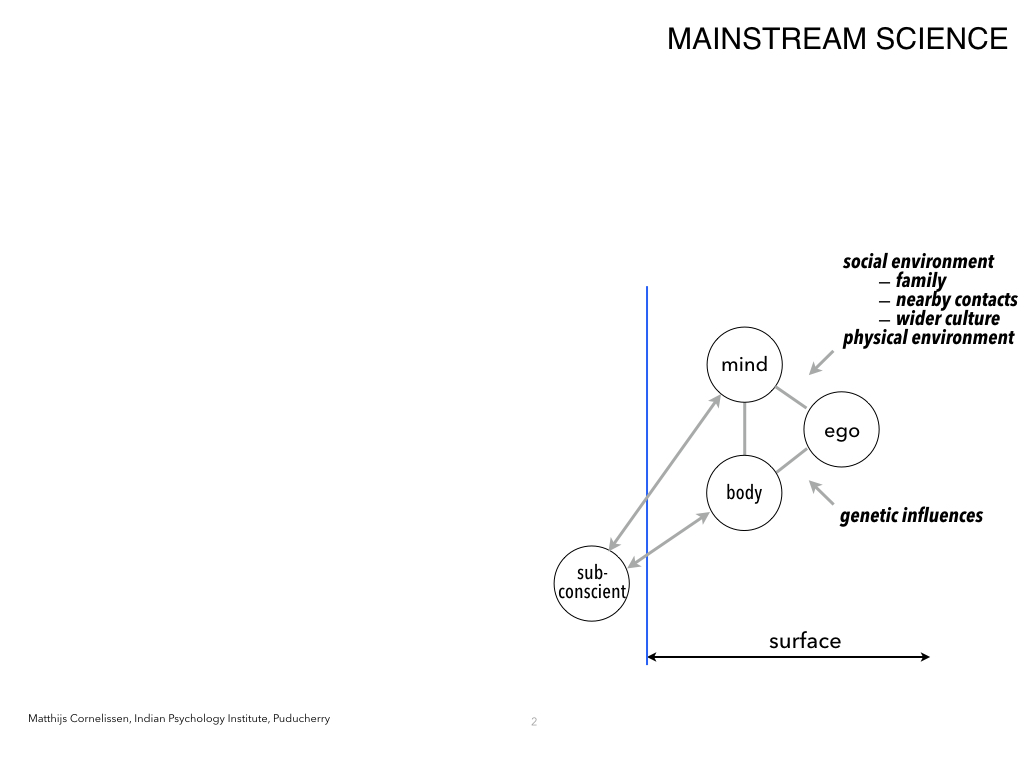

Fig. 1.3.1. Influences on individual development

— according to mainstream American psychology —

1. Influences in the social and physical domains

In Europe, the 18th century saw a lively public debate on two related questions. The first was whether man was basically, innately good and could only be spoiled by later influences, or innately evil and in need of the civilizing influence of society to become at least partially good. Rousseau supported the former view and formulated it rather elegantly by saying, "men are wicked, yes, but man is good". The various Christian religious authorities of the time strongly supported the latter; Calvin's followers going furthest in the direction of "original sin": the idea that man is by nature evil. The second question was whether the qualities of a man are there from birth, or inscribed later as on a blank slate or tabula rasa. Both questions are of course related and of public interest because the answers lead to very different ideas on upbringing, education and various other social and political issues. To name just a few: when people are intrinsically sinful, a strict regime of coaching and moral education is crucial; if they are basically good, education should allow children maximum freedom to develop under their own inner guidance. If differences in intelligence are socially determined, this would support arguments in favour of fostering intelligence to the maximum possible for all students. If there are large innate differences it would support efforts at designing different approaches to education for these different innate levels of intelligence.

The discussion was initially known as nature vs. nurture, but over time the nature pole got identified with the narrower concept of genetics. In the first half of the 20th century, a stress on genetics came to be equated with racism, and the two most influential behaviourist psychologists of the time, Skinner in the USA and Pavlov in the USSR were convinced that any child could be conditioned into any kind of citizen. Though this seriously overstated what "conditioning" could achieve, there are numerous studies supporting the power of influences from the surrounding. We'll refer to these in the section on education. On the other side, there are studies which seems to support the opposite view that an amazingly wide variety of human traits and propensities are genetically determined. The most picturesque of these are the older studies with identical twins (and other siblings) who show stunning similarities in spite of having been brought up in entirely different families. Over time more subtle in-between positions won ground and it is now commonly accepted that it is not a matter of either-or: genetics can set a baseline, or determine a certain range of possibilities, but it is nurture that determines which of those potentials will become manifest.

Mainstream modern science limits itself to what is accessible, or at least potentially accessible, in what is called the "ordinary waking consciousness". As a result genetic and environmental physical and social influences are all what this first diagram shows. The only exception is that we have included the "subconscient". As we have seen in the chapter entitled "The Self and the structure of the personality", the subconscious does not belong to the outer being but to the inner being. We have included it here as Freud discovered one dark corner of it, which he called the "unconscious", and at least in some universities Freud's theories are still considered part of mainstream psychology.2

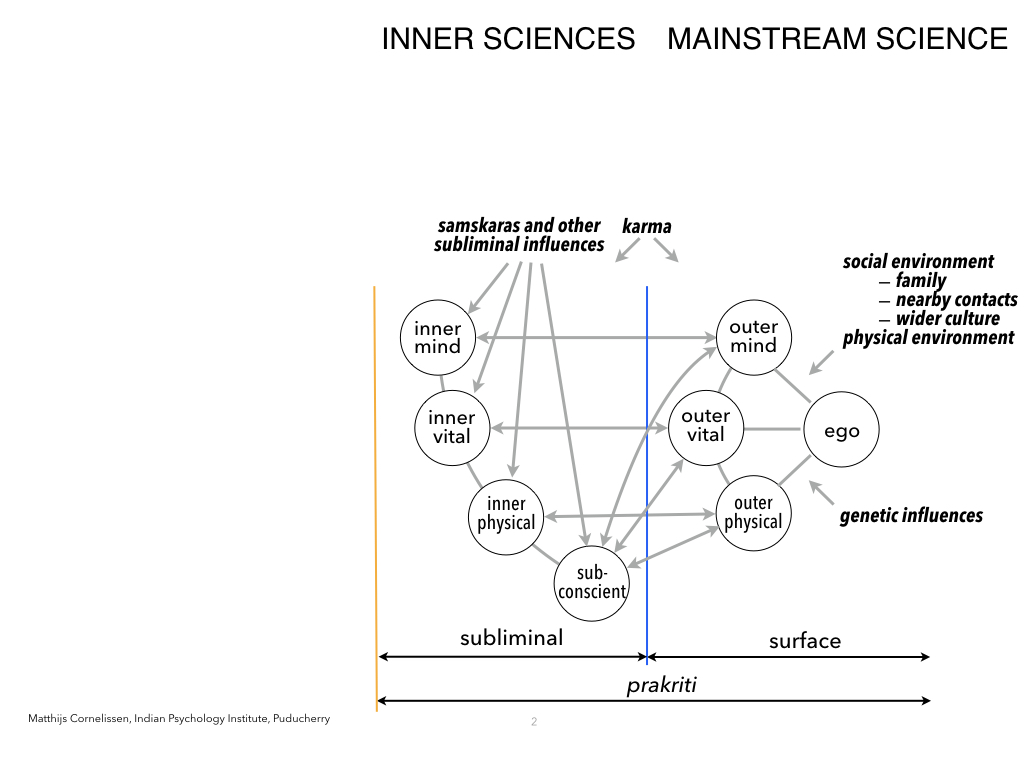

Fig. 1.3.2. Influences in the subtle realm of the inner being

— according to various Indian traditions —

2. Influences in the subtle realm of the inner being

In terms of territory, there are quite a few changes from the previous diagram. Most noteworthy perhaps is that the area where the subconscient is lodged has now got a name and has been more extensively populated. It is now called the "subliminal" to indicate that it is below the threshold of our normal waking awareness, and it contains besides the subconscient, an inner "mental", "vital" and "physical", which correspond to the Sanskrit manas, prana and annam. This division in three is already mentioned in the Ṛg Veda but perhaps best known from the way the Taittiriya Upanishad distinguishes the different kośas or "sheets" in the human personality.

On the surface of our personality, the mental, vital and physical tend to be mixed: our thoughts influence our feelings and body; our feelings colour our bodily sensations and our thoughts; and our physical state has an unmistakable effect on our thoughts and feelings. In the subliminal realm, however, the division in three is very obvious and stark. For people who live primarily in their mind, it is, for example, an amazing experience when they feel for the first time basic emotions like love, anger, desire, awe in all their vital intensity before they are mentalised and dressed up in words. The same is true when one becomes for the first time aware of the pure mind without any vital immixtures, or of the body's consciousness when both vital and mind are quiet.

Though the division in three is much less clear in our surface nature, in this diagram this division has been extended to the surface nature because doing so helps to understand motivation more clearly, especially in complex human interactions that would have been quite confusing otherwise. Roughly speaking, the vital part of our nature is into self-assertion, while the mind is into understanding. Confusion arises because pursuing mental objectives has a much higher status than pursuing one's personal vital agenda, so we tend to camouflage vital impulses by pretending that they come from the mind. We typically say "Why are you doing that?" when we mean "I don't like what you are doing; please stop it". In other words, when we actually want to pursue the vital objective of making someone else do what we happen to like, we cover it up by pretending to be involved in the noble pursuit of wanting to understand the other person. The same happens in more benign interactions. When we ask "How are you?" it hardly ever means we are genuinely interested in how the other person is doing. Most of the time we would be unpleasantly surprised if the other would give a detailed answer. What we really mean is "I'm a decent civilised individual with good intentions. Can we proceed to business?" And when the other answers with "Fine, what about you?" — which he may quite well say even when he is in a bad mood or deep trouble — we know the other is civilised too, and the deck is cleared for the real issues at hand. A few more complex examples from the academic world are given in a short chapter called, "A typical example".

In India, amongst the various samadhi and nirvana oriented spiritual traditions, the importance given to these three different types of consciousness and being differs because it is not really needed for a highly focused pursuit of purity, kaivalya: After all, if all one wants to do with one's nature is to quieten it, then one doesn't need to know much about it. A generalised rejection of all forms of emotional attachment combined with an extreme degree of mental discipline is then sufficient to make the intellect (buddhi) so sattvic and so similar in character to the absolute equanimity of "pure consciousness", that one can move as-if frictionless from a sattvic buddhi to the intrinsically pure puruṣa (Self). It is only if one's interest goes beyond liberation towards an integral transformation of the whole of human nature, that this simplification will no longer do and a more comprehensive understanding of human nature becomes necessary. As I've tried to explain in the chapter on Sri Aurobindo's concept of an ongoing "Evolution of Consciousness" and later in the chapter on "The Self and the structure of the personality", the essential difference between the mental and the vital forms of conscious existence becomes then of the greatest interest.

An important second point to keep in mind is that in Indian Psychology, the inner mental, vital and physical are not considered to be only parts of our individual nature: they are seen as part of independent, "objectively" existing worlds in which we are perhaps even more closely connected with others than we are in the physical outer world. In fact, Sri Aurobindo holds that the reason most people have so little telepathic capacity and empathy is not due to any chasm between people, but due to the wall we build inside ourselves between our individual surface awareness and our own inner nature. He holds that in our inner nature the psychological presence of others tends to be active whether we are aware of it in our surface nature or not.

A final point is that for clarity's sake I've depicted these three realms as simple circles, but each one of them is actually an extremely complex world with many internal divisions and complex interactions, both within themselves and with each other. On all this, there is some more detail in the previous chapter we already mentioned, "The Self and the structure of the personality", and we'll come back to it in the later chapters on Self-development.

In terms of influences, two additions have been added. The first is karma, the second "samskaras and other subliminal influences".

Karma

The concept of karma plays a central role in Hindu and Buddhist thought. The basic idea is simple enough: the fate that befalls us is not due to chance or a for us mortals not always understandable action from the Supreme, but to our own actions in the past. This much all theories of karma have in common. Beyond this, there are some quite different ways of understanding how exactly someone's actions affect the fate that follows.

A system of rewards and punishment?

By far the most common view of karma sees it as morality-based system of accounting: the more good things we do, the better our future fate; the more bad things we do, the worse our circumstances will be. As Sri Aurobindo points out, there are several serious problems with this theory. The most obvious is perhaps that it doesn't correspond to experience: In real life one sees good people faced by serious hardships and wicked people flourish. To explain this, reincarnation and a delay in the accounting system are brought up: the fellow who is now good, in spite of his admirable conversion, still suffers from his previous misdeeds. The wicked man, in spite of his sudden turn towards evil, still enjoys the fruits of a virtuous life lived long ago. Such poor management might be attributed to rather incompetent parents trying in vain to keep their children on a path of virtue, but they seem out of place as a description of how the Divine has made the world. Additional doubts may include that the actual mechanism is still not clear. The system seems to require an accountant-like personal godhead who doles out rewards and punishments according to a carefully maintained ledger. Another serious problem is that good and bad are known to be socially and culturally determined and as such not really suitable to support a serious cosmic law; and finally good and bad cannot be equated with pleasant and unpleasant. Good done in order to reap pleasant rewards is not as noble as it looks and lives lived for the sake of comfort and rewards may hardly be worth living. In short, this explanation of karma looks like a projection onto the cosmos of a rather unenlightened way of bringing up unruly children.

Karma as a morality-neutral system of cause and effect

There are other ways of looking at karma than as a morality-based system of rewards and punishments. Sri Aurobindo suggests that karma might work rather in a morality neutral way, like the forces in physics: actions simply produce reactions of the same type. There are two riders to this view that both follow from the conception of reality as a manifestation of consciousness. The first is that because we humans are active, conscious beings, an intention (seen as a force of consciousness) will have as much or even more impact than an outward act. The second is that actions "stick" to specific individuals to the extent that these individuals are emotionally involved with the action. An action done in a spirit of detachment and in harmony with the need of the moment, does not produce karma for the individual. The introduction of consciousness as force allows us, moreover, to avoid looking at karma from a perspective of helpless victimhood: It makes it possible to consider whether, at the level of our deepest conscious identity, we do not actually choose our fate to ensure our quickest and most complete spiritual growth. This is a rather complex issue with repercussions at the deepest level of the meaning and purpose of our individual lives, and we will come back to it when we discuss pain, love and detachment in the context of personal development and therapy.

Social consequences of a belief in karma

To conclude this first look at the concept of karma, it may be useful to give some thought to the role played by belief in karma, and the secondary gains and losses this belief brings about. Though I'm not aware of any conclusive research in this area, my subjective impression is that in India, over time the way people look at karma has changed considerably. From my little experience I would say that 50 years ago, the vast majority of the people in India had little faith in the possibility of having any direct influence on how their own lives would evolve, and the concept of karma was commonly used as justification for a lethargic attitude. There was a widespread belief that making effort made no sense as the law of karma had already pre-determined how things would go. The modern interpretation of karma is almost the opposite: it holds that past karma does no more than determining the present, while the future is determined by what we do now.3

An interesting aspect to believing that our fate is due to our own past actions is that it makes it easier to bear with misfortune. When one believes that a personal God or an impersonal Nature determines our fate, it is difficult to accept that people are born in such different cirumstances. Believing that ill fortune is due to our own actions restores a certain fairness and order to the world, and what is more, given that we are finite even in our capacity to do ill, we can expect our difficulties also to be finite: in a karma-driven universe, it is not possible to be doomed for all eternity, and once we have borne out the ill effects of our bad karma, we can expect to be free and enjoy a happy life again.

Unfortunately belief in karma can also make less caring. Somewhat in the same way as Darwin's "survival of the fittest", karma can be used as an excuse for the socially advantaged to abdicate their responsibility for and empathy with the less advantaged. To all these aspects of karma we will come back in the sections on self-development and reincarnation.

Samkaras and other subliminal influences

The English word that comes closest to samskara is probably "imprint". On the one hand, it is used for all you receive from the culture in which you grow up and especially for the social influences on your sense of what is right and proper. In that sense it is used more specifically for a series of rituals that accompany the development of an individual from conception to adulthood. On the other, it is used for influences from other lives that effect our present life. In between lives, they are supposed to be stored in subtle, inner worlds, from where the soul picks them up when it is born again. They can be collective and individual, positive and negative. Negative samskaras are sometimes seen as functioning in a similar manner as the traumata Psychoanalysis speaks about, except that they have a wider range: In terms of effect they are considered to effect circumstances as well as psychological states, and in terms of origin they can come from previous lives as well as from the present one. The word vāsanā is used in a somewhat similar manner as samskara for influences from the past except that it does not indicate such a definite formation (or deformation), but a more gentle tendency left by past experience. As it also tends to be used for more positive impacts, vāsanā gets then the meaning of inclinations and desires.

When do the inner influences have their effect?

Both from a practical standpoint and from the perspective of possibilities for research, an important question is when "occult" inner influences like karma and samskaras are supposed to play their role. The impression one gets is that as India becomes more and more "modern" and materialistic, there is an increasing tendency amongst the Western educated middle class to adopt a kind of hybrid understanding of reality. The world is then seen primarily as a closed, purely physical system that works in the way mainstream science claims it does, while things like karma and samskaras — to the extent that they are still believed in at all — are relegated to the metaphysical and religious domains. It is then held that if they exert an influence, it must be pre-birth, say by determining the circumstances in which one takes birth. If this were the case, they would remain intrinsically outside the scope of scientfic research (unless they would play a measurable role in the recombination of DNA strands at conception, but that is rather far beyond our present capacities of investigation). If the more traditional view holds true and samskaras exert their influence throughout life, then it might at least in principle be possible to discern and study their influence. We'll have a closer look at this possiblity in the chapters on research, self-development and education.

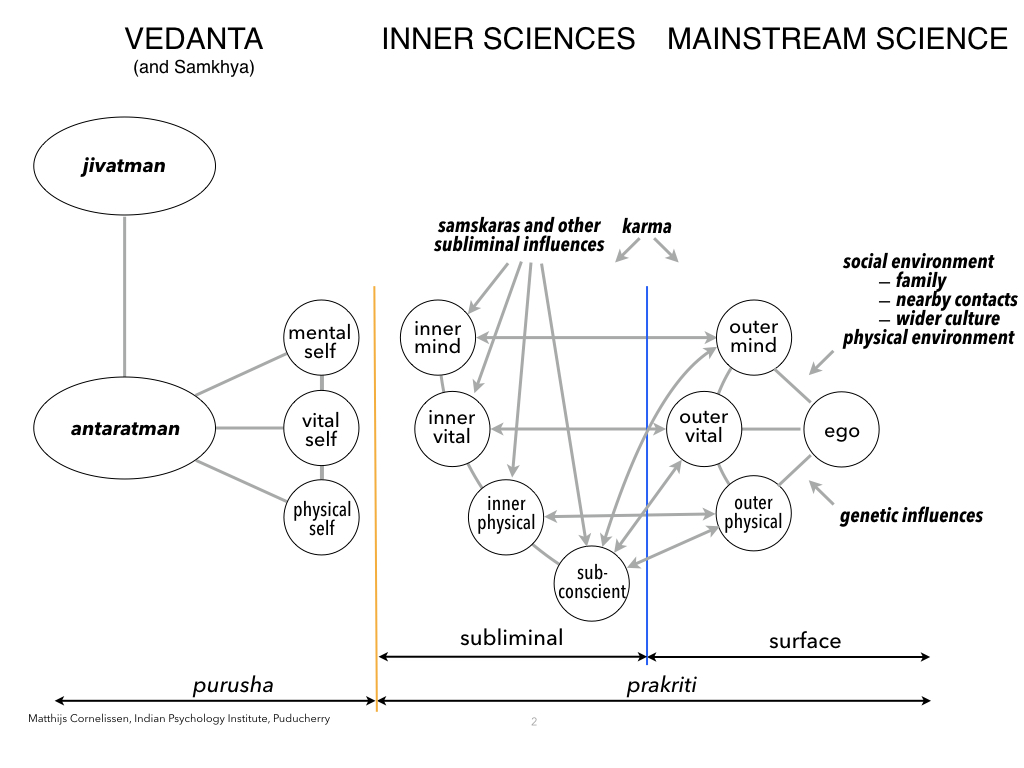

Fig. 1.3.3. The Self as presence and refuge

— according to most Indian traditions —

3. The Self as presence and refuge

The third diagram adds again a whole new section. It depicts the situation as seen by people with an experience or realisation of the transcendent aspect of the Self, the Divine, the Absolute, or whatever word or name we may give to the highest spiritual reality people can become aware of.4 The names and relationships depicted in this diagram are those of Advaita Vedanta and texts like the Taittiriya Upanishad. They have been explained in the chapter on the structure of the personality, but for our present purpose, these details actually don't matter. The relevant point is simply that some people, whether frequently, occasionally, or even just once in a lifetime, seem to come into contact with another kind of reality that gives them the certainty that there exists something that is not only infinite and absolute, but also infinitely good, beautiful, perfect, and blissful, and, what is more, in their deepest essence, they are one with That. The descriptions vary regarding the kind of absolute: they range from emptiness to fullness, from impersonality to Personhood, from universal Nature to pure Self, almost anything is possible. But there is a common thread, especially in the after-effect: such contacts tend to leave behind a sense of goodness, relaxation, diminished worry and concern over the endless ups-and-downs of ordinary life, a smile, a permanent quiet inner joy, and perhaps with all this, some less egoism, some more empathy, love and care for others. People who have had this experience tend to "light up", almost physically, like a bulb, when they're reminded of it. The visit to the "other reality" can be so short and fleeting that it can only be whistfully remembered as a vague and tempting possibility for the future, but it can also leave a considerable, permanent effect behind, signifying a definite turning point in life: something has changed once and for all in one's basic sense of who one is and how one is related to God and the world. It is then that it is called a "realisation" rather than an "experience".

Considering all this, we could describe the left side of the diagram as the part of our personality in which we know the Divine (or even have the subjective sense that we are one with the Divine), while the right side represents that part of our personality in which we do not know this. In Indian philosophy the realm on the left is often described as the realm of the puruṣa, the Self as carrier of our consciousness, while the right is the realm of manifest reality, prakṛti, Nature. Though the left is thus "the Self" while the right is "the world", calling it like that might create confusion as the little, lowercase "self", the self that most people most of the time identify with, is firmly on the right. What is on the left is not our ego-based "I", but the very core, the very essence of our consciousness. It is the ultimate reality which is described by different people in seemingly contradictory terms like the empty nirvana of the Buddhists, the infinitely-full paramatman of Vedanta, and the pure, transcendent puruṣa of Samkhya. There is more on these terms in the chapter on the Self and the structure of the personality.

There is however, still a problem at this stage. The attentive reader may have noticed that there is in this third diagram a gap between the innermost puruṣa section on the left, and the inner and outer prakṛti sections on the right: the different elements on the left are interconnected, and so are the elements on the right, but there are no cross-connections between the left and the right. The reason to depict it this way is that while there are many people who believe that there is something on the left, only few have a direct and continuous contact with it. This is not only a matter of personal experience: some philosophies and religions stress the gap between the world and the Divine and others the oneness between them. Dualist philosophies like Samkhya tend to stress the presence of this gap; monist philosophies like Advaita Vedanta more typically deny it. Amongst the major religions too, some stress the difference between man and God, while others stress the oneness.

In terms of experienced psychological reality, the gap is most trenchant when the individual comes into contact with the Absolute in a state of yogic trance or samadhi.5 The gap may then be so absolute that when he or she comes out of the trance there can be an inner certainty of knowing or being That but hardly any detail on what That entails. Even if in due time the two states come close enough for the individual to become to some extent aware of both simultaneously, the centre of one's identity still tends to be either here in the manifest world or there in the Transcendent: When here, the Transcendent may look — not anymore far, for once known it always feels intimate and near — but as if behind a veil, as if temporarily unreachable; and when there, this world may look vague, irrelevant, or plain unreal.

Corresponding ways of acquiring knowledge

Before we move on to the next stage where this gap begins to be bridged, there is one last thing, which is not depicted in the diagram but perhaps still of interest at this stage. It is that we know what is described on the far right side of these diagrams through our outer, physical senses, our sense-mind and our intellect. The material in the middle we can know through two different ways of acquiring knowledge: in the first type we know our inner nature pseudo objectively, as if we are looking at our own nature from the outside; in the second we know our nature experientially through a direct contact of consciousness with consciousness. The Divine on the left we can only know through what Sri Aurobindo calls "knowledge by identity". At present science uses only the first of these four ways of acquiring knowledge in a highly sophisticated manner. Of the second science uses only a notoriously unreliable naive variant, introspection. Of the third we use only a very small subset for skill-training. The fourth is not part of science at all. It may be clear that if we want to take psychology further, we need highly sophisticated versions of all four ways of acquiring knowledge. This issue has been taken up in some more detail in one of the chapters of Part Two.

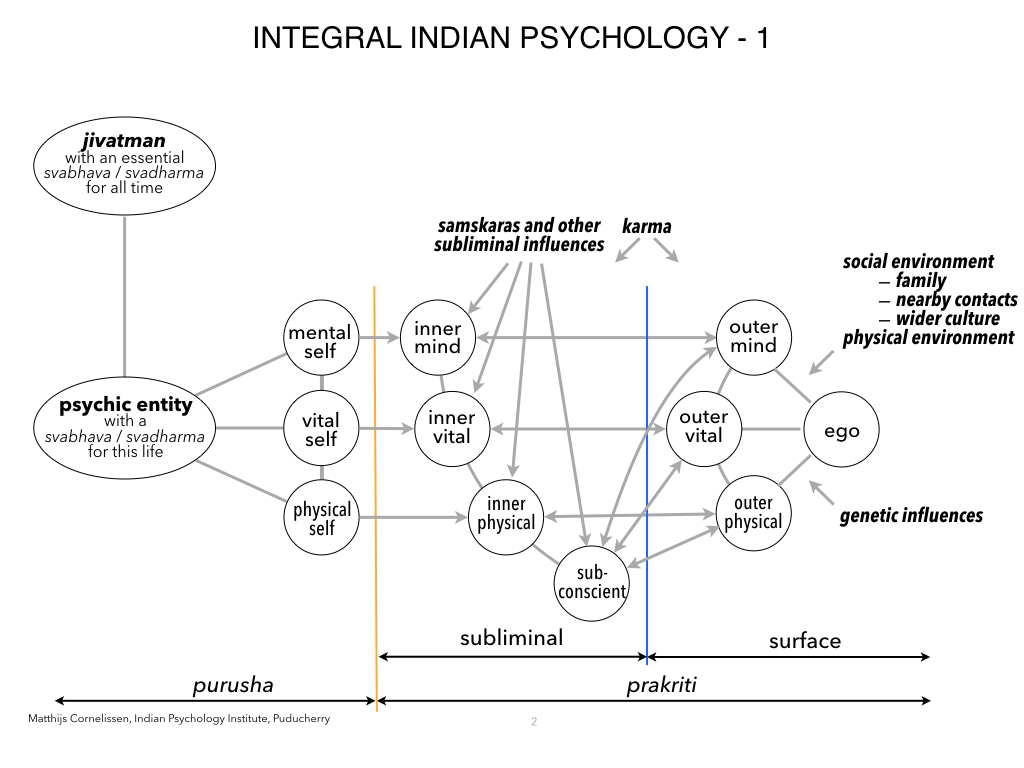

Fig. 1.3.4. The Self as influence

— according to integral Indian psychology —

4. The Self as influence

The next diagram depicts the Self as influence, and with this we have reached the most important part of the story. If the first diagram would have given a complete picture of all there was to our psychological reality, life would have been essentially mechanical and meaningless. One could even argue that it would have been plain monstrous given the suffering that is such an inalienable part of life in this world. Including the inner worlds as indicated in the second diagram would have not helped much, and might even have made life uselessly complicated. The third scheme with its possibility for individual redemption would have been good for a few individuals but it would not have fully solved the problem, for there would still not have been a meaningful explanation for the existence of the world. The basic solidarity that binds each one of us to all others would, moreover, still have tainted our individual escape with an air of irreality.

Fortunately, the Vedic rishis had a more profound understanding of reality. As we have described in the chapter on the evolution of consciousness, Sri Aurobindo followed their lead when he developed his theory for the manner by which the one universal Consciousness produced the differentiated many we now see in the world. He describes the involution which which must have preceded the evolution in which we now see happening around us as a two-step process:

- In step one, the original One makes many instances of itself;

- In step two, each of these instances limits itself through a process of exclusive concentration to a small subset of the infinifinity of qualities which the Divine has as a whole.

The interesting point of this theory is that it implies that each of these centers of consciousness is outwardly limited but in its essence still the Divine. One can see this perhaps most clearly in the inanimate world: even if an electron in its appearance and in its apparent action is no more than an electron, it still acts in perfect harmony with every law and every other thing in the universe, which, as we saw earlier, implies an implicit but perfectly adjusted omniscience. And this intrinsic harmony stretches into the life world. One sees it not only in rocks and rivers, but also in trees and forests. We see it even in simple animals: we see there the beginnings of mind, but this primitive mind is still subject to the harmony of the whole, so there is no disruption of that harmony. It is only with the arrival of humans (or perhaps a little before that) that things become problematic. On the one hand, we have individualised sufficiently to see ourselves as separate from the whole. On the other hand, our supposedly free mind is in reality still under the dominant influence of the self-assertive life-force. And the result is a dangerous hybrid: an egoistic semi-independence which can go against the harmony of the whole.

While this is no doubt a dangerous intermediate stage, the Vedic scheme implies that it is possible for us to take our independence one step further and free our mind from its subjection to the egoistic vital nature and from its own atavistic defects![]() . If we manage to do this, we can then use our growing freedom to go back into our deepest Self and reconnect with the original Oneness that supports and upholds the universe as a whole. As we saw at the end of the chapter on the evolution of consciousness and again in the chapter on the Self and structure of the personality, we have then two options. We can try to merge back into the original oneness — letting the drop lose itself into the ocean — or we can invite the ocean to reflect itself in the drop, consciously allowing the inner Presence of that absolute Oneness to influence our being and action in the world. Sri Aurobindo describes this second option as a triple transformation. First a "Psychic Transformation" which involves an increasing Presence and influence of the innermost Self, first on our inner nature and ultimately even on our outer nature. Then a "Spiritual Transformation" in which the nature is infused with the faculties and qualities from the higher spiritual layers of consciousness. And finally a "Supramental Transformation" which brings about "a strong and assured step forward in the spiritual evolution of the consciousness such as and greater than what took place when a mentalised being first appeared in a vital and material animal world" (LY — I, pp. 174–175).

It may be clear what far-reaching effects this would have both for the individual and for the society at large. We'll discuss some of the processes involved in this triple transformation in more detail in the chapter on self-development.

. If we manage to do this, we can then use our growing freedom to go back into our deepest Self and reconnect with the original Oneness that supports and upholds the universe as a whole. As we saw at the end of the chapter on the evolution of consciousness and again in the chapter on the Self and structure of the personality, we have then two options. We can try to merge back into the original oneness — letting the drop lose itself into the ocean — or we can invite the ocean to reflect itself in the drop, consciously allowing the inner Presence of that absolute Oneness to influence our being and action in the world. Sri Aurobindo describes this second option as a triple transformation. First a "Psychic Transformation" which involves an increasing Presence and influence of the innermost Self, first on our inner nature and ultimately even on our outer nature. Then a "Spiritual Transformation" in which the nature is infused with the faculties and qualities from the higher spiritual layers of consciousness. And finally a "Supramental Transformation" which brings about "a strong and assured step forward in the spiritual evolution of the consciousness such as and greater than what took place when a mentalised being first appeared in a vital and material animal world" (LY — I, pp. 174–175).

It may be clear what far-reaching effects this would have both for the individual and for the society at large. We'll discuss some of the processes involved in this triple transformation in more detail in the chapter on self-development.

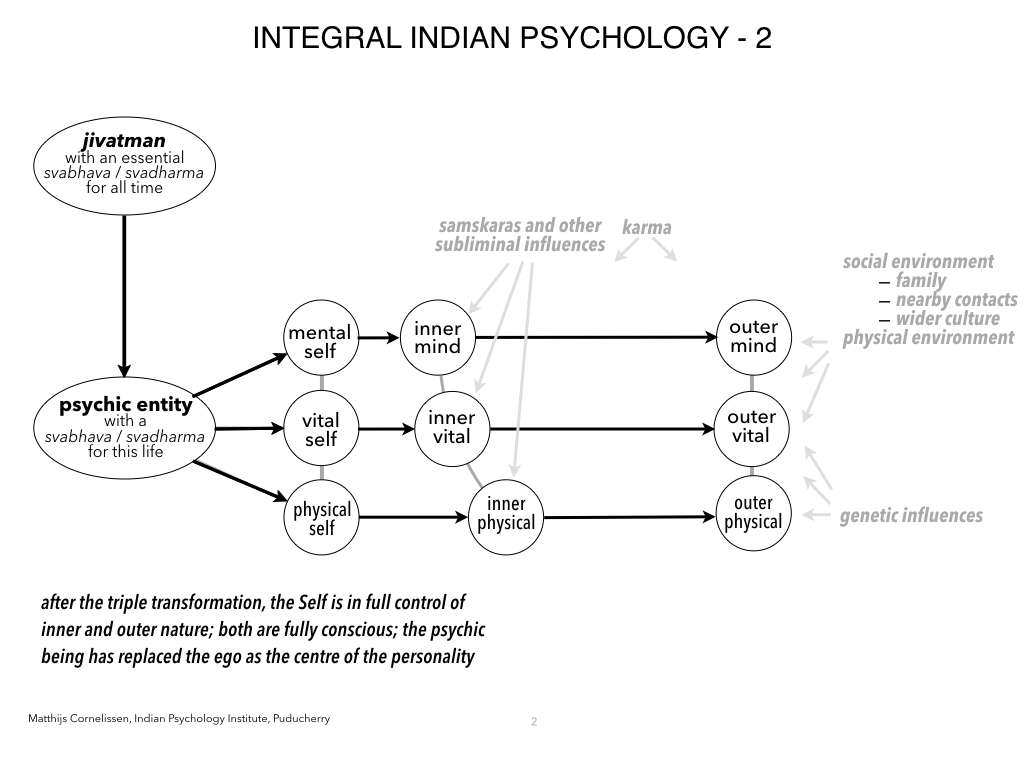

Fig. 1.3.5. The Self in control

— according to integral Indian psychology —

5. The Self in control

The last diagram depicts the next stage in the evolution of consciousness as envisaged by Sri Aurobindo. The various processes of transformation that are necessary to reach this stage have been completed, all functions of the ego have been taken over by the psychic being, and every aspect of the nature now works in full compliance with the new management. The subconscious is no more and the individual has become a fully conscious expression of the Divine.

We'll come back to some of the dynamic possibilities of this state in the chapter on action and agency, and we'll have a closer look at a few of the early stages in the process of transformation in Part Five: Working on oneself. For a description of the later stages of the transformation and for this state itself, I refer to the last four chapters of Sri Aurobindo's The Life Divine (pp. 922-1107).

To conclude

Before we close, I suggest we look once more at the first diagram. There he is, this little creature with his body, mind and ego, fixed in his grooves by his genes, his upbringing, his culture , trying to keep himself standing in an environment that is sometimes good to him, sometimes bad, but never fully under his control. What he doesn't realise that all the while he is pushed around by all kind of secret forces from inside, of which he has no knowledge whatsoever.

That's where our adventure starts. He is in trouble, he wants to find out what is happening inside, what it is that drives him... His trouble increases hundredfold. And then slowly slowly, from underneath the muck, from behind the darkness, little glimmers of light begin to come forward till he finds that deep, deep inside there is a source of Light, Joy, Beauty and Wisdom that makes the whole sordid adventure more than worth the trouble. Different versions of this story have been told in all times and all civilizations. Here is one, told and retold for thousands of years, called Samudra Manthan, or The Churning of the Ocean");?>.

Endnotes

1Just as there are many ways by which people approach the Divine, the Divine too appears to people in many different forms. Here is one of the most inspiring descriptions I know of the many forms in which the Master of Existence can come to meet us on the way.

2Though this is not really the focus of this text, there is some more info on the subconscious and how it relates to Freud's unconscious in part 4 of Appendix 1.2.1.

3This new version of karma is clearly more empowering and goes with the modern belief in personal achievement and success. It was well-rendered in a poster, put up throughout Delhi around 2010, "Our Time Is Now!" It expressed a sentiment that would have been unthinkable in Delhi thirty years earlier.

4The original meaning of samadhi is yogic trance, in other words, a state of absorption in the Absolute in which one loses one's sense-based awareness of the world. In some systems the meaning of samadhi has subsequently stretched to include a much wider range of spiritual end-states, including some that cannot really be described as trance. We are using the word here in its original sense.

To receive info on

Indian Psychology and the IPI website,

please enter your name, email, etc.